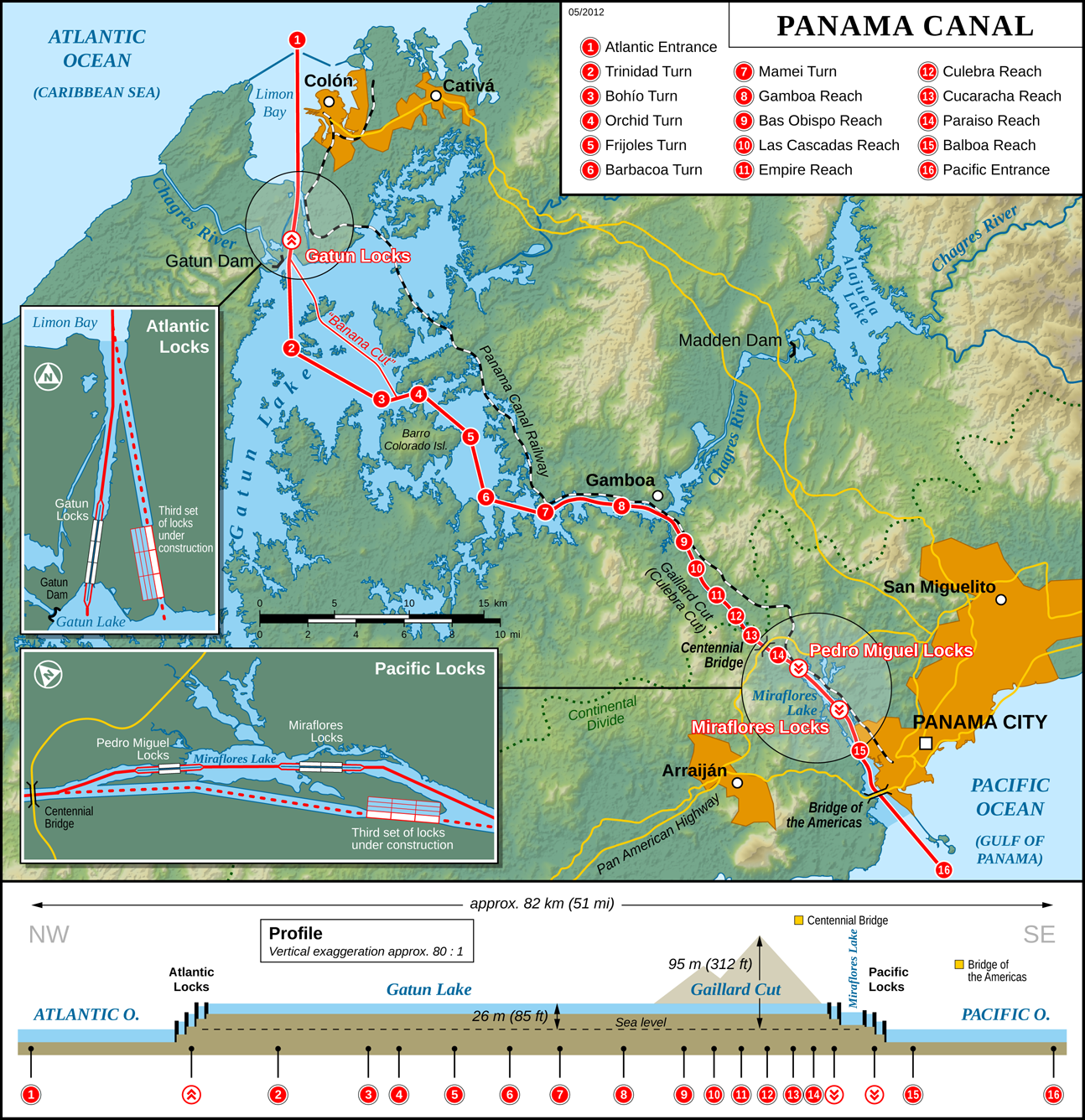

Building the Panama Canal took several attempts and 34 years. Today, 101 years ago, the SS Ancon was the first steamship to cross the 80 km-long Panama canal. After a failed French attempt, American army engineers took over in 1907 and decided that the best way to cross the isthmus was to build several dams, create a large artificial lake, and build a set of three locks on each end that lift the ships 26 meters above sea level into the Gatun Lake. Even though the Canal connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, it actually runs from north (the Atlantic side) to south (the Pacific side) and slightly west to east rather than east to west. Even today, crossing the Canal is a spectacular experience, one which I have had the pleasure to enjoy on a recent trip with the Jewel of the Seas, a 90,090 tonne cruise ship that fits through the locks with just centimeters to spare.

On my recent crossing through the Canal, we entered the Gatun locks (pictured above) on the Atlantic side. After proceeding through Gatun Lake into the Chagres River, we reached the Pedro Miguel and Miraflores Locks (pictured below) on the Pacific Side. It is an exciting crossing that showcases both the marvel of engineering that the Panama Canal represents, and the Canal's enormous strategic importance for international trade.

It is remarkable how massive ships are moved gently through the locks. Several electric trains on each side of a ship hold it in place with cables. As the ships are lifted up and down, the cables are always kept at the right level of tightness. When the ships need to move forward, the trains on both sides move forward in a marvelous display of synchronization. The picture below shows one of the trains and the cables attached to the Jewel of the Seas.

The map below provides an overview of the Panama Canal, with close-ups of the old and new locks.

click on image to enlarge; Source: Wikipedia Commons

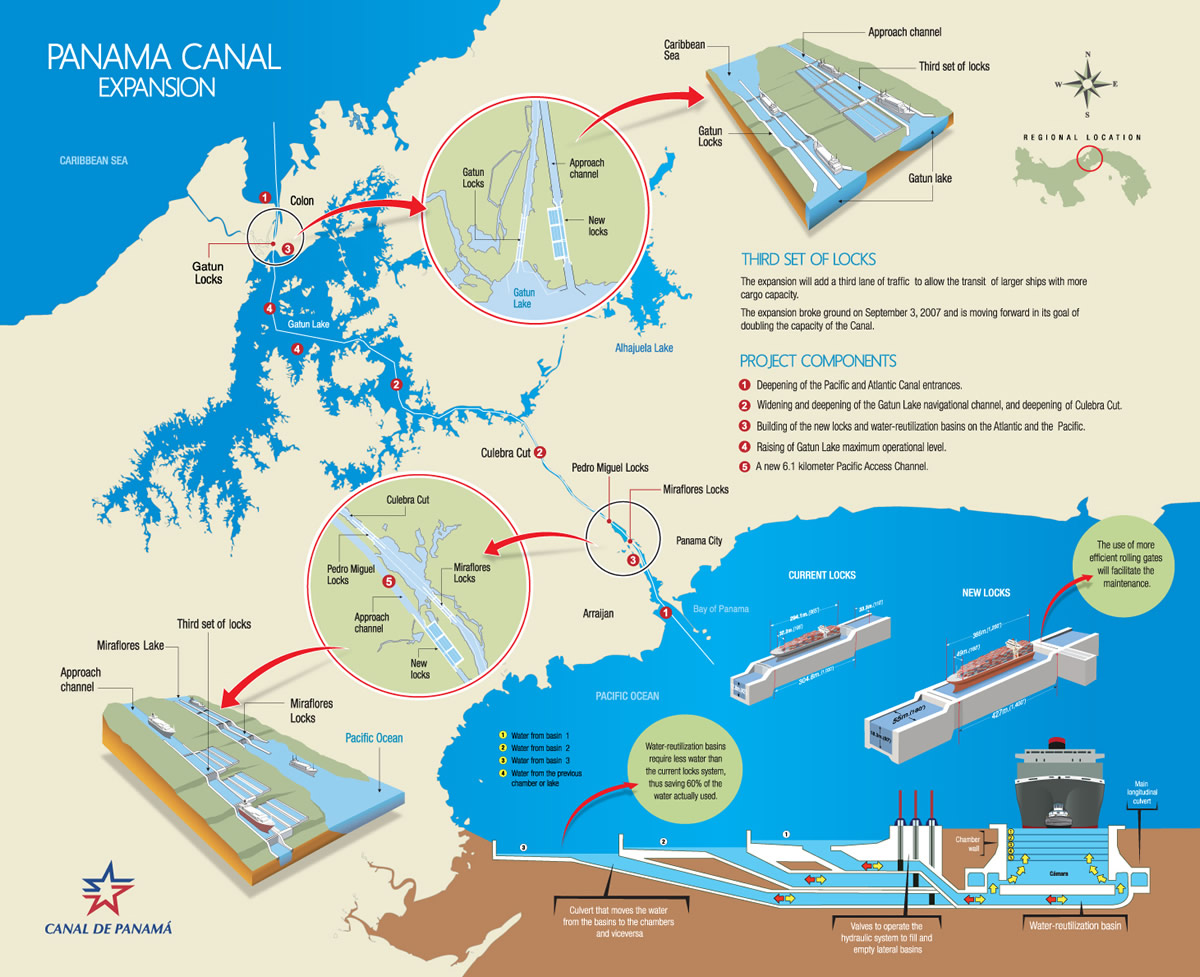

In 2006, Panama approved an expansion of the canal by building a new set of locks that are much larger than the old locks. Many modern container ships will be able to pass through the Panama Canal henceforth. However, some tall cruise ships such as the Oasis-class ships of Royal Carribean International will not fit under one of the bridges that span the canal. The limitation on the "air draft" of ships remains the same. The current constraints imposed by the Panama canal on ships is dubbed "Panamax". With the expansion, there is a new standard "Post-Panamax". The table below compares the two standards. The new locks are expected to open on April 1, 2016.

| Panamax | Post-Panamax | |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 294 m (965 ft) | 366 m (1,200 ft) |

| Width (beam) | 32.31 m (106 ft) | 49 m (161 ft) |

| Draft 1 | 12.04 m (39.5 ft) | 15.2 m (50 ft) |

| Air Draft 2 | 57.91 m (190 ft) | 57.91 m (190 ft) |

| Deadweight tonnage 3 | 52,500 MT | 120,000 MT |

| TEU4 (containers) | 5,000 | 13,000 |

Notes: m: meters; ft: feet; MT: metric tonnes. 1 in tropical fresh water. 2 distance from the surface of the water to a vessel's highest point. 3 deadweight tonnage measures the cargo that can carried by a vessel. 4 twenty-foot equivalent units.

The cost of putting a container through the Panama canal is USD 82 (effective 2011). A container ship with 4000 TEU would thus pay USD 288,000 for a crossing. In addition to the simple tolling by TEU, the Panama Canal Authority also uses the Panama Canal Universal Measurement System (PC/UMS) for assessing tolls on other cargo ships. 1 TEU is equivalent to about 13 PC/UMS tons. About 40 ships cross the Canal every day. Passenger ships, such as cruise liners, pay 134 USD per passenger berth. For example, a ship like the Jewel of the Seas with 2,500 passener berths would incur a toll of USD 335,000 per crossing.

It has been estimated that today only about 10% of the world containership fleet meets the Post-Panamax standard. However, already about three-quarters of the world's containerships that are being built or that are on order are Post-Panamax. Larger size brings significant cost advantages. There are economies of scale in shipping. Going from Panamax to Post-Panamax will save 25% on fuel cost per TEU. The charges for containers on Post-Panamax will be lower than the current rate.

The chart below, courtesy of the Panama Canal Authority, shows the stages of the lock expansion. Click on the image to enlarge it and to read the fine print. What is remarkable about the new locks is not only its size, but also the engineering ingenuity that helps preserve water in Gatun Lake. The new locks will require less water than the old locks, saving 60% of the water actually used.

The picture below shows the frentic activity on the new Miraflores Locks, which are slowly nearing completion. The target date for opening, April 1, 2016, still looks optimistic to me, however. I would not be surprised if the April date is delayed by several more months.

click on image to enlarge

As an international trade researcher, I was curious to find detailed statistics on what is going through the Panama Canal, and from where and to where. That information turned out to be rather difficult to obtain. The Panama Canal authority has some of the more recent data, but it requires a fair bit of processing. The question that I am interested in is how the opening of the new locks will increase and shift trade flows.

Another question is whether the Panama Canal will ever get a rival. The so-called "Interoceanic Grand Canal of Nicaragua", at about 450 km nearly six times as long as the Panama Canaal, looks ambitious and at a proposed cost of over $50 billion expensive for a relatively poor country such as Nicaragua, and only the financial backing of a Hong-Kong based firm seems to make this a potentially viable project. Competition would be good for business—as well as having redundancy from a geopolitical point of view. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen if this project will ever take off. What is certain, however, is that next year international trade through the Central American isthmus will get a big boost.

References:

- Panama Canal Expansion Project, official web site with web cams that show the progress

- Panama Canal Transit Statistics

- Panama Canal Tolls