Drinking and driving remains stubbornly one of the highest risk factors for road traffic accidents and fatalities. It is estimated that an average of 1,500 Canadians are killed each year in traffic accidents where alcohol was involved. The legal blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limit in Canada has remained 0.08-percent (i.e., 0.08 grams per deciliter). Now the federal government in Ottawa is considering lowering the limit, following related initiatives in some provinces. This change is long overdue. Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been advocating that nations adopt a BAC limit of no more than 0.05 g/dl, and 89 nations have already done so, including virtually all European Union countries. The Globe and Mail editors supported the federal government's move on August 13, and justice minister Jody Wilson-Raybould should indeed follow where the empirical evidence leads her.

Fell and Voas (2014) provide a good overview of the related questions and research answers, for those interested in the science. The relationship between BAC levels and accident risk is known as the Compton curve (Compton et al., 2002). This curve is exponential. A driver with a BAC level of 0.08 has a probability to be involved in an accdent that is 2.69 higher than when sober. For 0.05, the probability is 1.38 times higher—about half the rate at 0.08 g/dl. The curve also depends on age. Low doses of alcohol (lower than 0.05 g/dl) have a far more devastating effect on young drivers (age ≤ 24) than on older drivers.

Provinces and territories have introduced administrative penalties such as license suspension from 24 hours to 7 days or having to take an education course. These penalties kick in at 0.05 g/dl (and at 0.04 in Saskatchewan). Some provinces have zero limits for young drivers, which reflect the high incidence of traffic accidents among that age group. For the vast majority of people, social drinking (a glass of wine over dinner or two beers after work) will not put them over the 0.05 g/dl limit.

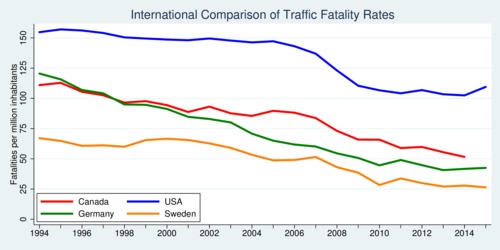

As the chart below shows, fatal road accidents have been declining in Canada and other OECD countries. Over the twenty year period between 1994 and 2014, road fatalities fell by about half, from 111 deaths per million inhabitants to 52 deaths per million inhabitants. That is significant progress, but it is the result of a combination of factors. Better laws and enforcement are an immportant part of it, but also safer vehicles and better road infrastructure. Interestingly, Canada does much better than the United States, where the rate of fatal vehicle accidents is nearly twice as high. However, there is clearly room for improvement. Germany, which has much denser traffic than Canada, has 20% fewer fatal road accidents, and Sweden's rate is an astounding 46% lower than Canada's.

click on image to

view high-resolution PDF version

Source: OECD (2017) Road accidents (indicator)

‘Laws that are enforced insufficiently are ignored and become ineffective.’

The number of road fatalities is disheartening. Impaired or dangerous driving causing death is a criminal offense in Canada with a maximum of 14 years of imprisonment, but that remains an insufficient deterrent. Motorists who drink and drive tend to be repeat offenders, and catching them is not easy. Any law is only as good as its enforcement. A law that is not enforced, or is enforced insufficiently, is ignored, disrespected, and becomes ineffective. Improving enforcement requires both labour and capital. More frequent sobriety checkpoints requires more police, but strategic use at the right time and place can make these more effect than random use. For repeat offenders, mandatory use of ignition interlocks may prevent further impaired driving. These ignition interlocks are highly effective, and thus mandating interlocks for all offenders, including first-time offenders, will improve effectiveness. Most jurisdictions in North America have Ignition Interlock Programs, including British Columbia. Referral to the IIP or the Responsible Driver Program are based on a point system in BC, and arguably the threshold is high so that only the worst offenders get referred. Wider use of RDPs and IIPs may help enforce and deter better.

Enforcement is also the key issue with respect to distracted driving. Cellphone use while driving is rampant and widely and incorrectly seen as a harmless practice. Accident statistics tell a different story. For the record: it is against the law to use any electronic device while driving unless it is hands-free. Increasing fines alone is not sufficient to deter distracted drivers. What are the chances of getting caught, after all? The federal government has taken notice. It has been reported that transport minister Marc Garneau is working on a tough new national standard to combat distracted driving. Smart enforcement strategies are needed. Recently, RCMP officers in Chilliwack and the Fraser Valley were hiding in utility-lift buckets, and other officers were riding in public transit to catch passing motorists who couldn't put their cellphones aside. So please, leave your phone alone while driving — no call or text message is worth risking your life or that of others.

‘Stricter laws and better enforcement must go hand in hand.’

Impaired driving and distracted driving is costly to all of us. Ultimately, motorists pay for higher accident rates through increased insurance rates. Investing in better enforcement can improve health outcomes as well as lower costs. Stricter laws and better enforcement must go hand in hand. This requires putting adequate resources into enforcement, and developing effective enforcement technologies. (See for example my blog speed enforcement through section control about a highly-effective method to control speed.)

Opposition to the 0.05 BAC limit comes from the hospitality industry, which fears losing customers. As the Globe editorial correctly points out, this is a uniquely North American problem, while European restaurants have no problems with the lower limit. Restaurants' share of revenue from selling alcoholic beverages is much larger than in Europe. This is a result of selling food at a discount while charging a 300-percent markup on beer and wine. Margins in the restaurant business are slim, and markups on food are often near zero. Selling alcohol is a profit center, but it is also a trap. The solution is to slim the beer and wine list and leave the high-price selections to sommeliers in high-end restaurants. Misinformed opposition from the hospitality industry should not stop sensible public policy from being adopted.

The federal government in Ottawa is on the right track to reduce the BAC limit in Canada. Science is on their side, and thus they should not feel discouraged by near-sighted opposition from self-interested lobby groups.

Further readings:

- World Health Organization: Drink-driving: the facts, 2013.

- Globe editorial: A lower alcohol limit for drivers is a smart move, The Globe and Mail, August 13, 2017.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Countermeasures that work: A Highway Safety Countermeasure Guide For State Highway Safety Offices, 8th edition, 2015.

- James C. Fell and Robert B. Voas: The effectiveness of a 0.05 blood alcohol concentration limit for driving in the Unitd States, Addiction 109(6), June 2014, 869-874.

- André Solecki with Katie Scrim: The Human Cost of Impaired Driving in Canada, Department of Justice Canada, 2016.

- Crashes and injuries, European Commimssion.

- Compton, R.P., Blomberg, R.D., Moskowitz, H., Burns, M., Peck, R.C. & Fiorentino, D. (2002): Crash rate of alcohol impaired driving. Proceedings of the sixteenth International Conference on Alcohol, Drugs and Traffic Safety ICADTS, Montreal.