Fifty years ago, on Sunday the 20th of July 1969 at 20:17:40 UTC, the Apollo 11 landing module touched down on the Moon. With the message "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed." the world learned that humans had arrived for the first time on Earth's nearest neighbour in space. When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took their first steps on the Moon a few hours later, it marked a historic moment that defined humanity's aspiration to grow beyond the confines of its own gravity well. Apollo 11 was followed by five more moon landings, putting a total of 12 people on the surface of the Moon. The magnificence of these landings is easily lost in our modern days of smartphones and powerful computers. The technical ingenuity to launch the powerful Saturn V rocket—able to lift 140 tonnes into space—and to ferry astronauts all the way to the Moon is perhaps one of the most remarkable achievements of the 20th century. Fifty years later, what have we learned from the Moon landings? Is there a rationale to return?

Sending humans back to the moons faces an obvious economic question: is it money well spent when robotic missions can accomplish the same for less? Shouldn't money be spent more on fixing our Earthly problems such as climate change? These are valid objections, but is there a case to be made for the expense and effort of sending people (and probably the first woman) back to the Moon, as NASA is now planning the Artemis mission for 2024 at the earliest? There are five main reasons, explored below.

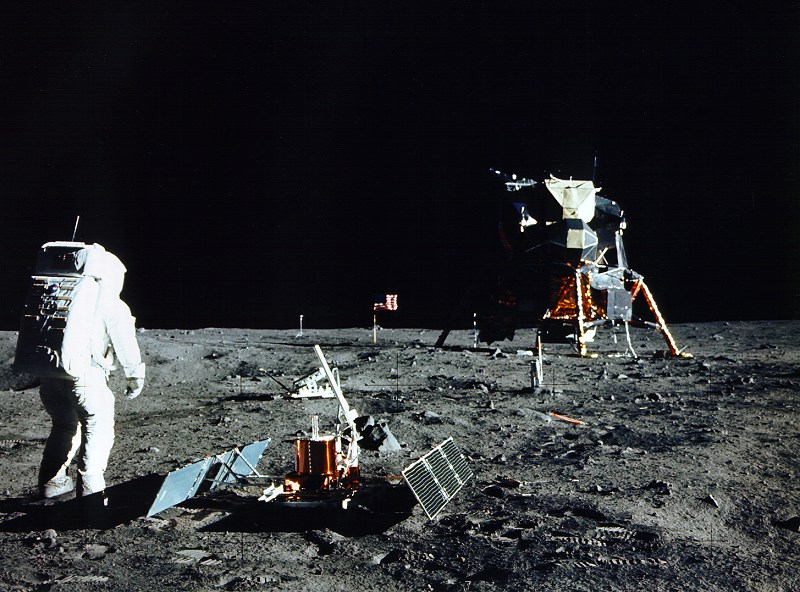

Apollo 11 on the Moon. Apollo 11 Launch. Source: NASA.

The Moon as Science Target

The Moon leaves many scientific riddles unanswered. The leading theory of the Moon's origin, the Giant Impact Hypothesis suggests that a Mars-sized object (named Theia) collided with the early Earth, with ejecta from the impact either merging back into today's Earth or coalescing in orbit into what is today's Moon. Jatan Mehta's article How the Apollo missions transformed our understanding of the Moon's origin provides a good introduction of this hypothesis. The hypothesis is still being refined. Natsuki Hosono and co-authors have explored the Terrestrial magma ocean origin of the Moon, suggesting that when the impact occurred, Earth was still covered in a slushy magma ocean. We also still don't know very much about the poles and the far side of the Moon, as Shannon Hall discusses in The Far Side of the Moon: What China and the World Hope to Find. Sending people back to the Moon could help answer the questions more rapidly than robotic probes, simply because landing humans requires larger equipment. Size matters, because humans would travel larger distances on the Moon, and collect and return more and larger samples. Making the case for human missions to the Moon are, implicitly, an argument for larger missions to the Moon.

The Moon as Science Base

The far side of the Moon is perhaps also a prime location for building astronomical telescopes, shielded from the worst of interference from Earth and unhindered by the filtering effect of Earth's atmosphere. Radio telescopes and infrared telescopes would be able to operate in a way that they are unable on Earth. Maintaining large equipment on the Moon will probably require frequent repairs, and who is better able to do this than a small team of astronauts?

Apollo 11 Landing Module on the Moon. Source: NASA.

The Moon as a Space Base

A base on the Moon could also enable missions to Mars by serving as a staging area. The much lower gravity and absence of an atmosphere may make the Moon an advantageous location for staging mission. As NASA points out, "the Moon provides an opportunity to test new tools, instruments and equipment that could be used on Mars, including human habitats, life support systems, and technologies and practices that could help us build self-sustaining outposts away from Earth." On one hand, a lunar gateway in orbit around the Moon may be the simpler approach. On the other hand, the Moon may provide resources that, if they can be turned into rocket propellant cheaply, could enable rocket launches from its surface.

The Moon as Natural Resource

Mining the Moon may well become economically feasible at some point. As NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory discusses, the Moon could provide water for supporting astronauts and providing rocket fuel; provide a rich source of rare earth metals; and in the far future provide a supply of the Helium-3 isotope that is expected to be the base for nuclear fusion. Berlin-based start-up company PTScientists recently signed an agreement with the European Space Agency and ArianeGroup to send an In-Situ-Resource-Utilisation (ISRU) mission to the Moon.

The Moon as Human Laboratory

Sending humans to the Moon to stay there long-term could also herald a new branch of medicine as we could study the effect of long-term exposure to reduced gravity, distinct from the micro-gravity that the current generation of astronauts is exposed to on the International Space Station. Would people be able to adjust to reduced gravity better than to weightlessness in Earth orbit? We will only know the answers to these interesting medical questions about the adaptability of the human body if we try. Whether such novel medical science leads to benefits down on Earth remains to be seen.

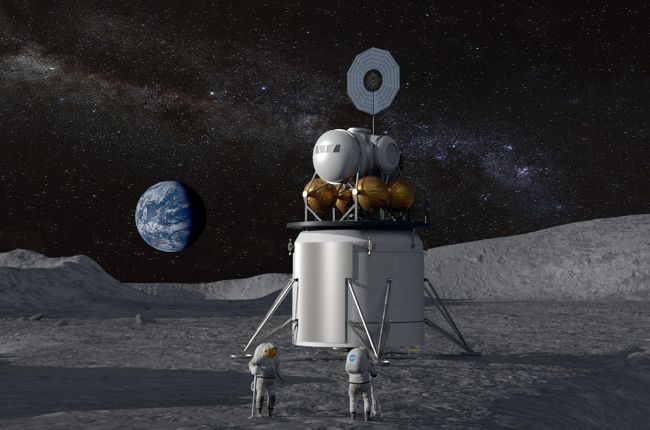

Artist rendering of future lunar lander. Source: NASA

Is a return of humans to the Moon likely?

Enthusiasm in the United States for sending people back to the Moon appear low, according to an AP-NORC Poll conducted in May 2019. 42% favor a return; 20% oppose it; and 38% are undecided. While there is a scientific case for sending humans back to the Moon, resource exploration will be beyond commercial viability for many more decades. Going back to the Moon as a human endeavour is ultimately an aspiration. Carl Sagan once wrote in Pale Blue Dot: "All civilizations become either space-faring or extinct." Well, I surely hope for the first of these two options.

Some also argue that we are at the beginning of a potential new "space race". China put a lander and rover on the Moon in 2013 and 2018. For the first time, a probe landed on the far side of the Moon, which required relaying through a satellite in orbit around the Moon. Namrata Goswami discusses China's space ambitions in a recent article in Strategic Studies Quarterly. China's ambitions include exploiting asteroids for resources, building space-based solar power, and establish a lunar base. Without better governance of space exploration beyond the existing Outer Space Treaty from 1967, there may be potential for international conflict and even a militarization of space. We are beginning to see the limitations of the treaty. My UBC colleagye Michael Byers has commented on Why Canada risks losing out on minerals in space. Article 2 of the Outer Space Treaty states: "Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means."—but this only applies to governments but not necessarily commercial entities. Byers makes the case for updating the Outer Space Treaty to provide new legal standards for space mining.

Ultimately, the cost of getting tonnage into space is driven by the economics of rocketry design. Elon Musk's SpaceX company currently has the lowest cost of getting cargo into space, thanks to the re-usability of its boosters and scale economies of producing the Merlin rocket engine. Competition is heating up, and commercial companies vying for lucrative earth-orbit business may ultimately help bring down the cost of space travel for humans as well. No less than three capsule designs are currently competing: SpaceX's Dragon, Boeing's Starliner, and NASA's Orion. This competition for designs and innovation will drive progress.

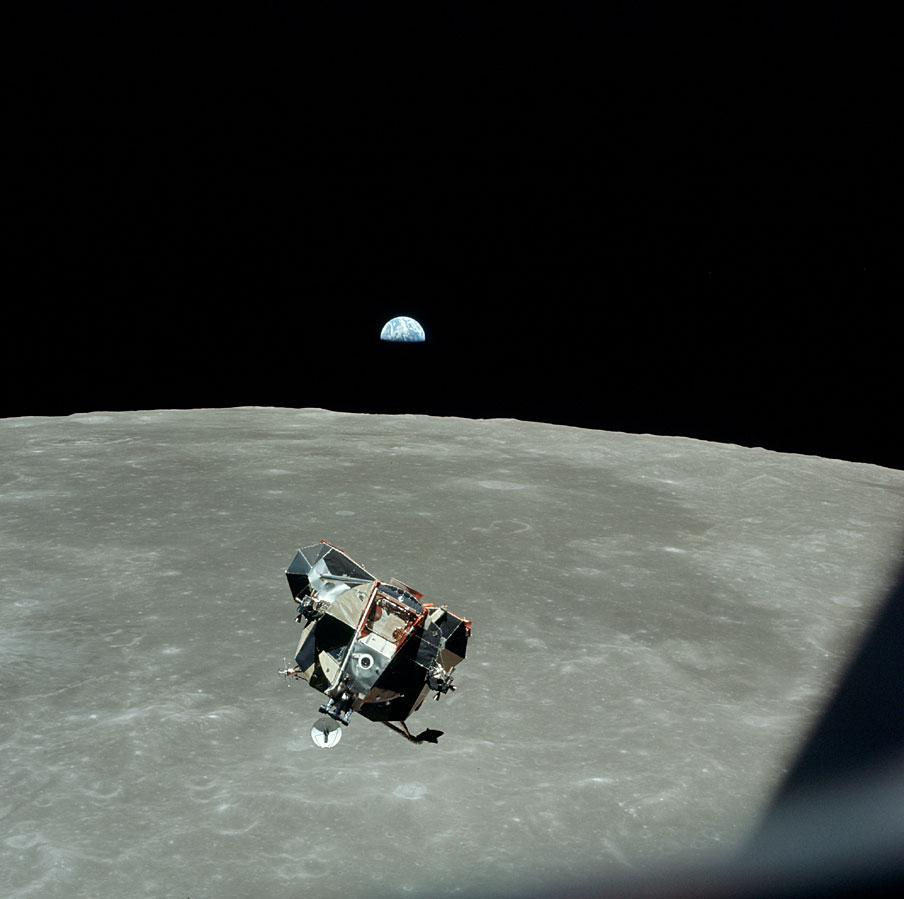

Apollo 11 Return from the Moon. Source: NASA.

I remember the last of the lunar landings in 1972. They endeared space exploration to a young boy. Fifty years later, the Moon landings continue to inspire because they remain a pinnacle of human ingenuity. As everyone who has ever uttered the phrase "if we can send people to the Moon, we can do anything" can attest to, the realization that just because things are difficult, they are not impossible, remains a powerful motivation to thrive for the best we can do—not just what is convenient or expedient or cheap or merely good enough.

Space enthusiast that I am, I do hope to see people return to the Moon in my life time, advancing science and international cooperation at the same time.

Further readings:

- Kenneth Chang: Why Everyone Wants to Go Back to the Moon, The New York Times, July 12, 2019.

- Miriam Frankel and Martin Archer: To the moon and beyond 1: What we learned from landing on the moon and why we stopped going, The Conversation, July 3, 2019.

- Graham Kendall: Would your mobile phone be powerful enough to get you to the moon?, The Conversation, July 1, 2019.

- Nadia Drake: Should Neil Armstrong's Bootprints Be on the Moon Forever?, New York Times, July 11, 2019.

- Ian Whittaker and Gareth Dorrian: US wants a crewed mission to the moon in five years – but can and should that be done?, The Conversation, April 8, 2019.