The global energy landscape is changing rapidly, and Poland is an interesting country to study in this regard. It's a very insightful case of "climate change meets geopolitics". Poland faces a dual transition: (1) reducing the country's carbon footprint by transitioning away from coal; and (2) diversifying the country's energy imports in order to manage geopolitical risks and reducing import costs.

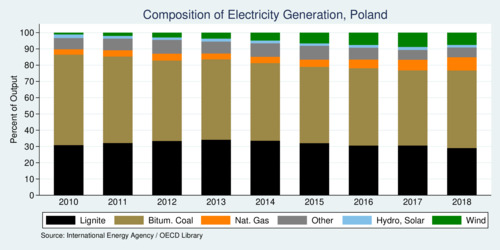

Poland's carbon footprint is worse than many other industrialized countries because of the country's heavy dependence on coal. The chart below shows that lignite and bituminous coal still account for the vast majority of electricity generation. Renewable energy supply is expanding (mostly wind farms) and is gaining share, but weening the country of its domestic coal will be difficult. Whereas natural gas is used much for home heating, its share in terms of electricity generation remains small.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) plays an important role in Poland's energy transition. This week Poland's state gas company PGNiG signed a 20-year LNG deal with Port Arthur LNG (Sempra Energy) for the supply of 2 million tonnes per annum (MTPA). This follows in a wake of similar deals in the past years. Poland has started importing LNG from Qatar and increasingly from the United States. The objective of LNG imports is twofold. First, long-term gas contracts were signed at a time when natural gas prices were high, and meanwhile spot prices have become more attractive. Diversifying imports allows Poland to reduce costs eventually—although initially there are costs for building import terminals where the LNG is regasified. Poland has built an LNG import terminal in Swinoujecie with an initial capacity of 3.7 million metric tons per annum (MTPA), and with expansion in progress. Second, moving to LNG allows Poland to reduce its dependence on imports from Russia, which have raised strategic concerns.

‘Increasing LNG imports also marks a geopolitical shift.’

Poland has looked for diversification of its natural gas supply ever since a 2009 shutdown of a natural gas pipeline that was supplying natural gas to Europe via Ukraine, with a conflict over pricing. Poland got caught in the middle of this conflict. This 3-week shutdown was costly to Poland and the country has been committed ever since to reduce its energy dependence on Russia. In 2019, Poland's imports of natural gas from Russia dropped to 60% of its total supply, with LNG imports rising to 23%.

Increasing LNG imports also mark a geopolitical shift—away from Russia and towards the United States. Poland's current government, formed by the national-conservative Law and Justice Party, has found itself politically drawn to the current US administration and more often at odds with its European Union partners.

Poland also had concerns about the Nordstream 2 pipeline through the Baltic Sea that will deliver natural gas from Russia directly to Germany when it is coming online as expected in 2021. The pipeline will bypass Poland. Germany, in turn, relies on Russian natural gas to facilitate its own transition to renewable energy and reduce its dependence on coal. However, the current US administration has opposed the pipeline and even imposed sanctions on firms engaged in the project. These sanctions have infuriated the German government. Poland's move to diversify its natural gas supply comes in the midst of this geopolitical repositioning.

‘The Baltic Pipe will diversify Poland's natural gas imports even more.’

In addition to building LNG capacity, Poland will also import natural gas from Norway through the proposed Baltic Pipe. This new pipeline is expected to become operational in late 2022 at the earliest—although with the typical construction delays 2023 seems like a safer bet. The Baltic Pipe is now close to being fully financed (worth €1.6 billion), and all the required permits are in place. Once completed, the Baltic Pipe will change the geopolitical context of energy markets in Eastern Europe significantly because Poland will also build interconnections to Lithuania and Slovakia. The Baltic Pipe has a maximum capacity of 10 billion cubic meters per year, which is equivalent to 7.4 MTPA of LNG imports. In addition to building LNG capacity, the Baltic Pipe will diversify Poland's natural gas imports even more.

Poland's geopolitical issues with Russia are closely linked to its existing contract with Gazprom, which is due to expire at the end of 2022. This contract required Poland to import a minimum of 8.7 billion cubic meters of gas. Replacing this volume with LNG would amount to 6.4 MTPA. Strategically, Poland would be able to replace Russian imports with a combination of imports from Norway, Qatar, and the United States. While it would not make Poland "energy independent", broadening the country's import portfolio will make it less dependent on any one country. It is a prudent exercise in risk management.

‘Natural gas is needed to displace coal and support the transition to more renewable energy in Poland.’

The geopolitical energy issues are also mixing strongly with the need to reduce Poland's carbon footprint. As the diagram above showed, reducing the share of coal in the generation mix is a tall order. While renewable energy is expanding, it also needs to be backed up with peaker plants. Poland's coal plants work more like traditional base load and cannot be ramped sufficiently fast to back up renewable energy. As wind power expands, more natural gas combined cycle plants are needed for the dual reason of backing up renewable energy and for displacing the more polluting coal.

All these factors combine to give natural gas a bright future in Poland, especially if it can be imported at lower cost than in the past. If US gas is cheaper than what Gazprom can deliver (some sources claim a 20-30% discount on US imports), the goals of import diversification and lowering import costs align. If Poland renews the contract with Gazprom past 2022, it will surely be on more favourable terms for Poland. Yet, natural gas demand is likely to rise, and a well-diversified import portfolio will also include Russian gas if the price is right. And if Poland wants to stay on track of EU targets to decarbonize its electricity generation, it will need to rely on expanded imports of natural gas to meet these targets.

Poland's official targets (Policy Energy Policy to 2040) call for a reduction in the share eof coal to 56%-60% by 2030 an increase in the share of renewables to 21-23%. Interestingly, the main tool for reducing carbon dioxide emissions will be construction of Poland's first nuclear reactors. The PEP-2040 plan actually reduces the initial target for nuclear capacity from 5.6 Gigawatts (GW) to just 3.9 GW, while boosting the capacity of natural gas plants from 2.7 to 5.3 GW.

Further readings and information sources:

- Weaning Poland off Russian gas, The Economist, 4 April 2014.

- Stanley Reed: Burned by Russia, Poland Turns to U.S. for Natural Gas and Energy Security, The New York Times, 26 February 2019.

- H.E. Evans and A. Easton: Poland revises draft energy policy to 2040, S&P Global Platts, 8 November 2019.

- Xiaodong Wang et al.: Poland Energy Transition - The Path to Sustanability in the Electricity and Heating Sector, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 2018.

- Jo Harper: Can Poland break Gazprom's hold on Europe?, Deutsche Welle, 27 March 2019.