On June 11, 2016 Walmart announced that it would suspend accepting Visa credit cards in its stores. Given its size as a retailer, Walmart's move was seen as a sign of a wider battle between merchants and credit card issuers about the magnitude of service fees. Visa fought back immediately with an open letter to Walmart, which was published in major newspapers. In the letter Visa alleges that Walmart simply wants a sweeter deal than other merchants and that Walmart is "dragging millions of Canadian consumers into the middle of a business disagreement". The battle between Walmart and Visa may be just that, but the problem about credit card fees transcends this dispute. Canadians pay a hidden tax on everything they buy with their credit cards, as the merchant fee is passed through to consumers. The cost of clearing payments is small—as the low transaction fees for debit card prove. So what do Canadians get in return for their high credit card fees? Credit card companies have been ratcheting up the benefits they pay out: air miles, loyalty points, or simply cash back. This money comes right out of your own pockets. These benefits are subsidized by people who pay cash or use debit. The problem is thus: credit card companies bind customers by offering more and better rewards, and this puts an upward pressure on fees. The solution is painfully simple: limit transaction fees to covering the cost of clearing transactions, and get rid of the plethora of so-called rewards and benefits. Put the money saved back into the pockets of Canadians.

Visa has a very large market share among credit cards in Canada (about 3/5), followed by Mastercard. Other provider such as American Express and the Discover Network have quite small market shares. Merchant fees are relatively high in Canada. While large retailers tend to get a significant discount, smaller merchants end up paying more.

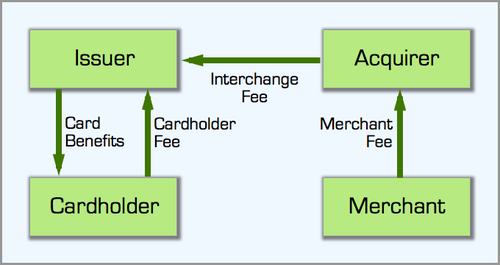

The diagram below shows the nature of the two-sided market for credit card payments. Issues issue credit cards to cardholders. Acquirers are separate entities that sell credit card handling services to merchants, such as Moneris and Chase Paymentech. The acquirer pays the issuer a fee, and recovers that and its own cost through a merchant fee from the merchant. Cardholders may also pay annual fees to the issuer, although many credit cards are without such fees. In return, the issuer usually offers benefits and rewards in the form of goods (e.g., reward items for points), services (e.g., insurances), or simply cash back.

click on image to view high-resolution PDF file

Economic theory does not quite tell us exactly how large an optimal interchange fee should be. Economic theory tells us that there are network externalities as credit cards become more valuable to consumers when more merchants accept them and more valuable to merchants when more consumers use them. In other words, the optimal interchange fee is not simply just the fee for producing the transaction service. An efficient interchange fee may subsidize one side of the market at the expense of the other side in order to generate a socially-optimal number of transactions. More competition is not simply the answer to interchange fees that are too high. Issuers focus their competition on market share, which puts upward pressure on fees because issuers want to offer more and better rewards than their competitors.

‘For credit card fees to come down, Canadians must give up their love of credit card rewards.’

Linda Lapointe, member of parliament for Rivière-des-Mille-Îles, sponsored a private member's bill, Bill C-236 An Act to amend the Payment Card Networks Act (credit card acceptance fees), which if passed would confer on the federal cabinet (the Governor in Council) the power to set a limit on the credit card acceptance fees that a payment card network operator may charge a merchant. Other jurisdictions have already moved in this direction. Foremost among them is a new Interchange fees regulation adopted by the European Union on June 8, 2015. Its articles 3(1) and 4 stipulate that paymeent service providers shall not offer or request a per transaction interchange fee of more than 0.2% of the the value of transactions for debit cards. or more than 0.3% for credit cards. Member states are allowed to set even lower caps. Canada could follow suit. For credit card fees to come down, Canadians must give up their love of credit card rewards. Once regulation is in place that limits credit card fees, issuers will lose their interest in the arms race to bigger and better rewards. Credit cards will turn back into what they really are (a) a payment clearing device and (b) an instrument to obtain credit. Perhaps we will see a drop in credit card use and a rise in debit card use. Interac Debit, possibly in conjunction with mobile payment systems such as Apple Pay, will fill the void. Declining credt card use may also help reduce consumer debt, which has reached dangerous levels in recent years.

Issuers have already conceded one important point in April 2015, when they committed to lower rates in response to new rules from the Government of Canada that includes disclosure of contract terms and merchant fees. But this was only a face-saving exercise without significant economic repercussions. Linda Lapointe's proposed bill would enable the federal government to intervene, and ultimately cap credit card fees. But if they do so, don't be sorry about losing your credit card rewards. Features that you find beneficial, such as insurance, you will need to pay for through an appropriate annual fee. There is no free lunch, especially when you are carrying a credit card.

- Ann Börestam and Heiko Schmiedel: Interchange Fees in Card Payments, European Central Bank Occasional Paper Series 131, September 2011.

- Heiko Schmiedel, Gergana Kostova, and Weibe Ruttenberg: The Social and Private Costs of Retail Payment Instruments - A European Perspective, European Central Bank Occasional Paper Series 137, September 2012.

- Diane Brisebois: Visa v. Walmart: Credit card fees need to be capped - for small and large businesses to thrive, The Globe and Mail June 17, 2016.

- Find information about rates: VISA, Mastercard.

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)