Sixty years ago, on 25 March 1957, a group of European countries embarked on a journey that has brought great prosperity to a continent that was still recovering from the tragedy of two World Wars during the first half of the 20th century. The six countries that signed the Treaty of Rome laid the foundation for the Common Market that ensured the free movement of goods, people, services, and capital. It created a customs union that established a common external tariff on imports from outside, and created free trade within that customs union. The achievements of the European Union, which now encompasses 28 member countries, are manifold, but none is more important than bringing together an entire continent to embrace the shared values of liberal democracy and human rights.

Celebrating a 60th anniversary is no small accomplishment. As coincidence has it, my parents just celebrated their 60th ("diamond") wedding anniversary this month. It is a wonderful moment to be able to look back at their journey together and say that it has been all worth it, in joy and happiness, but also with the many little and big challenges of life. Happy diamond anniversary, mom and dad, and happy diamond anniversary, European Union!

The last few years have been challenging for the E.U. The debt crisis in some member countries turned into a wider crises about the Euro as a currency, and yesterday Great Britain invoked the Treaty's Article 50 to start exit negotiations. It may appear that all is not well with the E.U. Onlookers from the outside may see crisis and bickering, but they may miss the bigger picture of how deep European integration has advanced in six decades. European institutions and policies reach deep into the fabric of law, commerce, and democracy.

Some pundits predict that Britain's exit will unravel the European Union. I disagree strongly. I am indeed not optimistic that Britain's negotiations with the E.U. will run smoothly. The time-line (2 years) is very short to accomplish what both sides probably desire: a new framework of partnership. The odds are stacked against success, as a new agreement needs approval by national parliaments. Unanimity is a high standard, and thus chances are high that Britain could end up without an agreement in two years if some countries block it. One possibility would be to extend the time-line, which is feasible. Hold the clock and keep on negotiating rather than walk away with nothing. For the E.U. the dilemma is that making concessions to Britain will open the door for other countries to ask for the same. This is a kind of "most-favoured nation" principle: the concession you give to one you have to give to everyone. The E.U. won't be able to yield much to Britain as a result, unless the E.U. is willing to take the negotiatins with Britain as a starting point for introducing greater flexibility into its structure that will benefit all E.U. members. If Britain's divorce from the E.U. ends up without a free-trade deal or some form of "associate status" with the E.U., it would be bad for Britain and the E.U. alike as businesses hold off on investments and trade faces new barriers as WTO rates would apply. Uncertainty is bad for business, and deeply integrated supply chains across the British Channel would rupture. Both sides have a strong incentive to come to a positive agreement. Whatever the outcome of these difficult and painful negotiations, one can hope that it may give rise to an evolution of the European Union.

Image Source: Wikipedia Commons. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution.

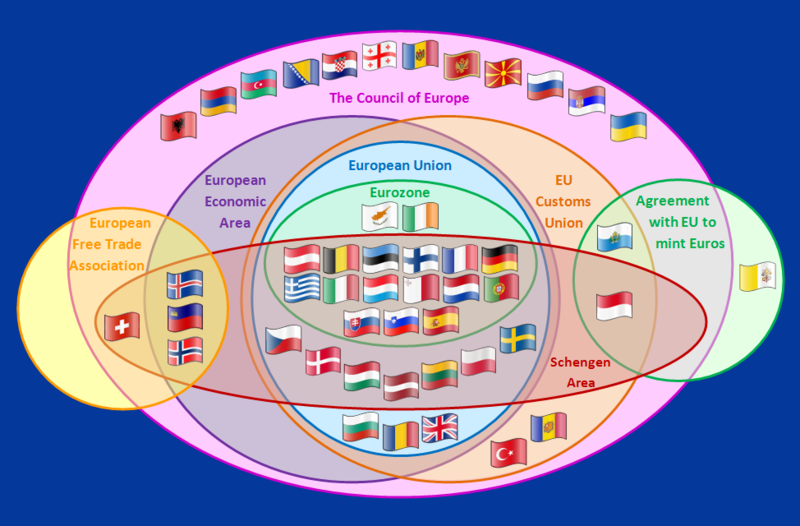

Paradoxically, Britain's exit from the European Union may end up making the European Union stronger and more resilient. Over the decades, the E.U. has actually morphed into an array of overlapping institutions that include a number of non-member countries (see the diagram above). Some E.U. countries take part in the Euro zone, others don't. Some non-member countries share access to E.U. markets through the Economic European Area and the European Free Trade Association. Some non-member countries are part of the Schengen agreement that provides border mobility. Europe is already a complex network of relationships rather than a homogeneous block. The logical conclusion is that Europe's multi-speed system will widen. Some countries will opt to integrate closer, and others will opt for less integration. The challenge will be to provide a stable framework for such multi-speed or multi-tier relationships, one that is elastic enough to absorb occasional shocks. The Economist magazine's John Peet argues the same case: "A more differentiated Europe, based around the idea of variable geometry, a range of speeds or concentric circles, would be a good way to ease the tensions and problems that afflict the present, overly rigid EU." The core group of countries would continue to remain deeply integrated (along with using the Euro), providing an array of more flexible associations at the periphery. Some have lambasted this idea as unworkable, considering E.U. membership a take-it-or-leave-it proposition, and any deviation from that principle as cherry-picking. That logic is flawed, however. More integration comes at a benefit, and the core gets to set the rules that outsiders have to follow, at their cost. Staying outside the core therefore comes at a cost, and some countries may be willing to pay this price, while others prefer the benefit of tighter integration. Norway is outside the E.U., yet opts to pay about a billion Euros a year to Brussels to gain access to the market, and has no say in the rules. Britain, pre-Brexit, pays 14 billion pounds to Brussels, about twice as much per person as the average Norwegian. It is likely that in order to retain access to the Common Market, Britain will end up paying a membership fee.

As Europe moves into the future, I am confident that a more robust framework for membership and association will emerge, one that can accommodate Britain. Europe is like a big family: there is some squabbling and some complaining, but at the end of the day Europe is still a family by virtue of shared geography and history and culture. Much has been written about the reasons and consequences of Britain's exit from the E.U., but it is most definitely not a sign that the European Union is a failed project, or is near collapse. Au contraire, the E.U. has grown through many challenges and problems, and because of resolving these challenges and problems. Today is not different. Despite claims to the opposite, the European idea is alive and well. An article in The Independent last year asked What has the European Union ever done for us? and gave seven cogent answers. Among them is the simple reality of geopolitics: together, Europe is stronger; divided, it is weaker. Today, the European Union is needed more than ever as a bulwark of liberal democracy, a defender of human rights, and a source of prosperity (occasional hiccups notwithstanding). That is especially true when the White House in Washington is occupied by an isolationist without a serious appreciation of international affairs.

Further readings:

- John Peet: Creaking at 60: The future of the European Union, Special Report, The Economist, March 25, 2017.

- James Kanter and Steven Erlanger: E.U., Pressured from Inside and Out, Considers a Reboot, New York Times, March 1, 2017.

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)