Neomercantilism, to use the definition found in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, is a revived theory of mercantilism emphasizing trade restrictions and commercial policies as means of increasing domestic income and employment. And mercantilism, popular during the 16th to 18th century in Europe, was an economic policy aimed at amassing gold and silver by the state through maintaining a positive trade balance. It was characterized by high import tariffs, especially on manufactured and finished goods, the hallmark of protectionism. Mercantilism and protectionism use similar measures to influence the trade balance, so it may be difficult to distinguish between them. Ultimately, both see trade as a zero-sum game: one country's gain is another country's loss. Both are also fixated on trade balances as the measure of success or failure. Neomercantilism is the 21st century update of mercantilism of the renaissance: it share with it the idea of achieving or restoring a nation's "grandeur". The link to nationalism makes mercantilism and its modern counterpart particularly worrisome. It is this added political motivation that lifts current U.S. trade policy from run-of-the-mill protectionism to neocmercantilism. It is intended to uproot the rules-based system of international trade that has been built over the last 70 eyars and replace it with a simple "might is right" approach to extract concessions from trading partners.

‘In a trade war, nobody wins. Trade is not a zero-sum game.’

In recent months, the Trump administration in the United States announced new tariffs, first on steel (25%) and aluminum (10%). These tariffs were launched with the justification of protecting "essential security interests", under US trade provisions known as Section 232 Investigations as well as under the provisions of Article XXI(b) of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Considering that Canada was not exempted from these tariffs even though Canada is a close military ally, this argument is not only implausible, it is also insulting to Canada. The framers of the GATT stated clearly that Article XXI was to be interpreted narrowly so that countries could not, under the guise of security, put on measures which furthered commercial interests. Of course, US trade measures are being challenged through the World Trade Organization, but this is a slow process. Several countries have already filed challenges that cite other GATT articles that are being violated. Countries that are hurt by these new tariffs strike back with countermeasures. Canada announced retaliatory tariffs that are aimed at the US to back off from its tariffs. The European Union and China did likewise. This is the beginning of tit-for-tat protectionism.

A full-blown trade war is becoming ever more likely. The Trump administration is doubling down on its threats: it wants to target the automobile sector with a 25% or even 35% tariff. Whereas steel and aluminium tariffs are a nuisance that have limited economic impact, tariffs on automobiles hurt the economies of Canada and Mexico severely. The U.S. administration thinks that it can bring jobs "back home" through these tariffs. With countermeasures following promptly, the U.S. will not gain jobs. Instead, some jobs will actually leave. Today, the New York Times reports that Harley-Davidson, Blaming E.U. Tariffs, Will Move Some Production Out of U.S.. Of course, that makes goods business sense for companies such as Harley-Davidson: move production where it can't be hurt by tariffs. It has been widely reported that Mr. Trump doesn't like German cars. In a meeting with French president Macron he allegedly said that he would continue his policies "until no Mercedes models rolled on Fifth Avenue in New York". Well, does Mr Trump know that Daimler manufactures its Mercedes GLE and GLS class SUVs in Vance, Alabama? Similarly, BMW produces its X-series models in Greer, South Carolina, and Volkswagen assembles vehcles in Cahattanooga, Tennnessee. These jobs will remain relatively immune to import tariffs.

There is one simple truth: in a trade war, nobody wins. International trade allows nations to specialize by focusing their production where they have comparative advantages. Reduce tariffs and integrate international supply chains, and everyone gains. Globalization has generated unprecedented wealth on the planet by allowing open countries to participate in the world economy. Neomercantilism is on course to destroy these gains in the false hope of extracting a greater share of this wealth for one country.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

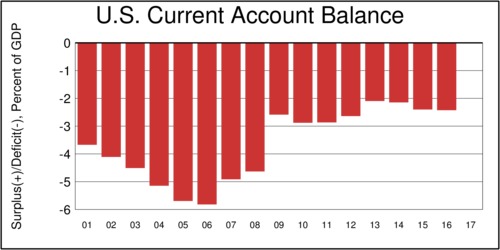

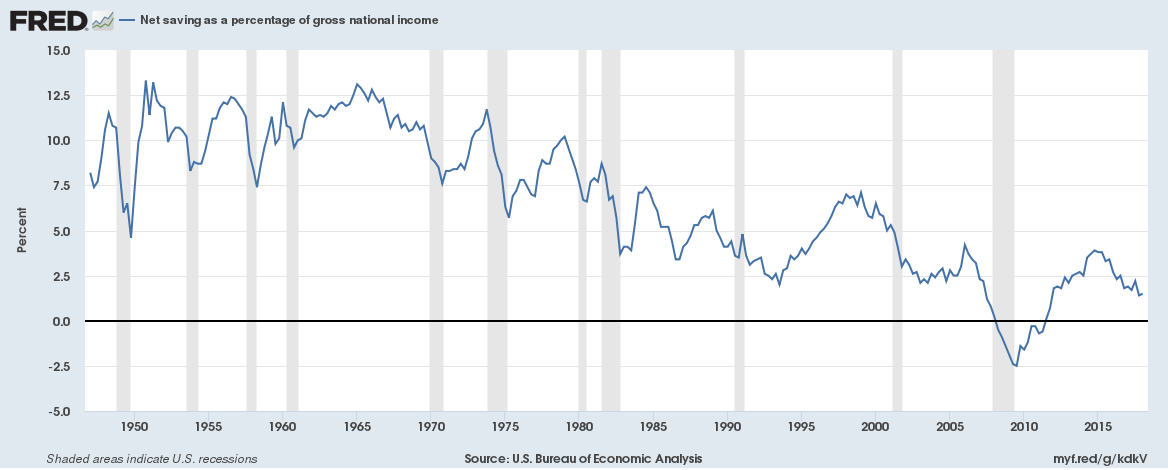

The obsession about trade deficits is one of the identifying characteristics of neomercantilism. It is true that the United States has a large trade deficit, or more broadly, a current account deficit. The diagram above shows that its magnitude today is not as alarming as it was a decade ago. As students of international trade know, when a country has a current account deficit, domestic investment exceeds domestic savings. The gap is made up by importing capital, and thus the United States has a capital account surplus (inflows are larger than outflows). The problem of the United States is not that it exports less than it imports, but that the country has a low savings rate. The trade deficit is merely a symptom of a low domestic savings rate. The measure for this is Net Domestic Savings as a percent of GDP. Net savings are obtained from gross savings by subtracting the depreciation of capital The diagram below, obtained from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis [source], shows the declining trend. There is an active discussion about whether this is a cause for alarm (Lawrence Summers and Chris Carroll: Why Is U.S. National Saving So Low?, or whether this trend is more benign (C. Alan Garner: Should the Decline in the Personal Saving Rate Be a Cause for Concern?). Even if it is not overly worrisome, the fact remains that the U.S. has been saving less than other OECD nations. Even the investment rates is below the OECD average, which suggests that the United States is not investing enough into its future. Net savings are down to a significant extent because the US government has been running an oversized budget deficit for too long.

click on image for fulls-scaleversion

There is yet another reason why the United States will run a perpetual trade deficit, and this has nothing to do with low savings. The United States remains in the world's supplier of liquidity as countries hold US Dollars as their favourite reserve currency. This means that the United States prints greenbacks in exchange for goods and services. Countries that want to hold reserve currency do so by letting the United States buy goods and services from them in exchange for US currency. This is a very advantageous position for the United States: get goods and services in exchange for printed paper. Of course, the party ends should countries give up on the US Dollar as their preferred reserve currency. This does not look likely any time soon, however. As a result, the US will continue to run modest trade deficits in exchange for supplying reserve currency. This is an enviable position to be in that should please US politicians. Why it bothers the current US administration seems to be a result of its neomercantilist dogma that sees a trade deficit as a sign of weakness, not strength.

So while the US administration is embarking on neomercantilist policy and its futile effort to "make America great again" (it already is a great nation), they focus on a non-existent problem (the trade deficit) while ignoring the much more significant problem (the secular decline of the net savings rate). US workers will suffer the consequences, along with their counterparts in the rest of the world. Trade war will spread the pain everywhere. Trade war is all pain, no gain. The future of our economies is shaped in our laboratories and by our infrastructure, and that means investment and innovation. Trade wars are not known to accelerate innovation. If anything, trade wars create greater uncertainty and slow down investment. Sadly, these simple macroeconomic lessons seem to be lost on the current U.S. administration.

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)