Does carbon pricing work? The answer is unequivocally yes. If Canada wants to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, we need to put a price on carbon emissions. The economic principle, putting a price on a negative externality that closes the gap between private and social cost of the pollutant, is not only true in theory but also works very well in practice. The federal government's revenue-neutral carbon pricing system is going in the right direction. If Canada wants to be serious about meeting its Paris Agreement obligations, a price on carbon is by far the best policy. As a market-based instrument, it is more efficient than command-and-control mandates and standards. Even better, the revenue neutrality turns carbon fees into carbon dividends that make less affluent households realize financial gains.

So how do we know that carbon pricing works in practice? We have had carbon prices in British Columbia in 2009. At first glance it looks as if BC's carbon price has not done much because total emissions have barely budged: total GHG emissions still hover around 64 Megatonnes per year. However, per-capita GHG emissions have significantly fallen, from 16 tonnes of carbon dioxide per person in the early 2000s to about 13 tonnes per person in 2017. BC's carbon tax has lowered per-capita emissions, but population growth and economic growth have offset these gains. The $30/tonne level that was in place between 2012 and 2018 was insufficient. It is now rising to match the federal target of $50/tonne by 2022. The beneficial effect of the carbon tax is also visible through another channel: BC's per capita emissions are lower than other provinces (controlling for differences in industrial composition).

‘The cross-country empirical evidendence is clear: higher gasoline prices improve fleet-wide fuel economy.’

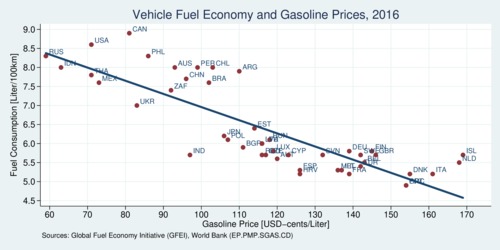

Carbon prices work—but at what level? Some of the best evidence we have today doesn't come from direct carbon pricing, but from indirect carbon pricing through gasoline taxes. There is large variation in gasoline prices around the world because of difference in gasoline prices. The Global Fuel Economy Initiative (GFEI) collects data on fuel economy of vehicle fleets around the world. Combined with data on gasoline prices, a clear picture emerges: as gasoline prices rise, fuel efficiency improves. The diagram below shows the evidence based on data from 2016. The horizontal axis shows gasoline prices in US-cents per liter; the vertical axis shows fleet-wide fuel economies in liters per 100 kilometers [L/100km]. The negative relationship is strong; the R2 of the linear regression is 0.65.

click on

image to view high-resolution PDF file

Special thanks to Blake Shaffer for the idea for this diagram.

The linear regression of fuel economy on gasoline prices reveals that for each 10 US-cent per litre increase in gasoline prices, fleet-wide fuel consumption falls by 0.34 L/100km. One can also estimate the gasoline price elasticity of fuel economy; it is –-0.57, with an R2 of 0.72. This means that a 10% increase in gasoline prices leads to a 5.7% decrease in fleet-wide fuel consumption.

In the diagram above, compare Canada's 8.9 L/100km fuel economy with Germany's 5.8 L/100km. Because fuel consumption is directly linked to carbon emissions, the average Canadian automobile emits about 50% more carbon dioxide than the average German automobile. Germany's fuel price in 2016 was about C$1.86/L, compared to C$1.09/L in Canada—a 77-cent difference. According to Global Petrol Prices, today's prices are about C$1.37/L in Canada and C$2.03/L in Canada, a 66-cent difference.

Gasoline taxes are, of course, not just carbon taxes. They are also fees for road construction and maintenance, and tax other negative externalities such as road congestion. Canada and the United States enjoy some of the lowest gasoline prices in the world, but this comes at the cost of having one of the worst fuel economies of vehicle fleets. North Americans like their cars big, heavy, high-powered, and gas guzzling. Transitioning to much better fuel economy is possible—but it comes at price: North Americans have some of the worst per-capita GHG performance in the world.

Would Canada have to raise its gasoline prices to European levels to achieve the same fuel efficiency? As battery technology becomes cheaper, the shift to electric vehicles may leap-frog the development. Canada may not need to raise gas prices quite as high as those in Europe to catch up. Shifting to EVs would lower GHG emissions significantly in Canada because of Canada's clean (mostly hydro) electricity. Fast-tracking EV adoption through other means than carbon pricing along may help overcome obstacles, such as with EV charging. There are additional market failures that need fixing; see also my blog BC needs a "right to charge".

How high do carbon prices need to rise? The 2019 report Closing the Gap: Carbon pricing for the Paris Target from the Parliamentary Budget Officer models the necessary increases in Canada-wide carbon prices (assuming that prices are the same all across the country, but with agriculture exempted). A fter reaching the $50/tonne target in 2022, an additional carbon price rising from $6 per tonne in 2023 to $52 per tonne in 2030 would be required to achieve Canada's GHG emissions target under the Paris Agreement. A carbon price of $102/tonne in 2030 would be equivalent to about 23 cents per liter of gasoline.

‘To reach the Paris Agreement targets, the PBO estimates that carbon prices in Canada need to rise to $102/tonne by 2030.’

At the federal election in two weeks, Canadians have an important choice to make. Carbon pricing works, and works better than alternative policies. A revenue-neutral carbon fee and dividend system, as is in place now, is by far the best option to pursue climate action. Canceling the federal carbon price would be a massive step backward. Canada needs to do its bit to fight climate change. Carbon prices lower emissions domestically, but they also create markets for climate solutions. As these markets grow world-wide, the prices of technologies falls through further innovation and global economies of scale.

The $100/tonne target by 2030 that the analysis by the Parliamentary Budget Officer has found is likely insufficient to reach the target of net-zero GHG emissions by 2050. As far as emissions from the oil sector are concerned, carbon pricing isn't the only tool available. The proposed federal Clean Fuel Standard (CFS) is a performance-based approach to reduce the carbon intensity of fuels and energy in Canada. As my colleagues Mark Jaccard and Chris Ragan have put it, "the federal Clean Fuel Standard (CFS) represents one of the biggest opportunities to use regulations to drive deep emissions reductions." CFS may complement carbon pricing if raising the carbon price becomes politically impossible. British Columbia has a CFS since 2019, requiring refiners and importers of fuel to meet a carbon intensity limit.

‘If Europeans can live comfortably with gasoline prices over $2/L, why can't we?’

The proposed federal CFS is similar to a cap-and-trade approach because the targets can be met flexibly through a market mechanism that involves tradeable credits. However, regulatory regimes tend to be complex and the credit trading system may become opaque if the underlying carbon accounting is not fully reliable. Much depends on the details of implementing the CFS. The oil industry is worried that the proposed CFS could ultimately entail higher economic costs compared to pure emission pricing. As the CD Howe Institute's Ben Dachis put it, there could be a Speed Bump Ahead: Ottawa Should Drive Slowly on Clean Fuel Standards. In my view, a carbon price is ultimately more transparent and efficient, and also covers the entire economy. Arguably, a carbon price requires much education to become politically acceptable across all provinces. The beauty of the federal carbon fee and dividend system is also that it helps less affluent households; it actually makes many of these households better off. And lastly, if Europeans can live comfortably with a gasoline price of over $2/L, why can't we?

Further readings and sources:

- Brad Plumer and Nadja Popovich: These Countries Have Prices on Carbon. Are They Working?, New York Times, April 2, 2019.

- Dale Beugin and Chris Ragan: The real costs and benefits of carbon pricing, MacLeans Magazine, 30 April 2018.

- Mark Jaccard and Chris Ragan: This time, let's set climate targets — and achieve them too, Vancouver Sun, 4 October 2019

- Government of Canada Pricing pollution: how it will work, web site as of 2019-07-11.

- Parliamentary Budget Officer: Closing the Gap: Carbon pricing for the Paris target, 13 June 2019

- Parliamentary Budget Officer: Fiscal and Distributional Analysis of the Federal Carbon Pricing System, 25 April 2019.

- Clean Fuel Stadnard: Proposed Regulatory Approach, June 2019.

- Benjamin Dachis: Speed Bump Ahead: Ottawa Should Drive Slowly on Clean Fuel Standards, C.D. Howe Institute E-Brief, 19 July 2019.

- Blake Shaffer: When it comes to vehicles, Canada tops the charts for poor fuel economy, Driving.ca, May 12, 2019.

- Jesse Good: Carbon Pricing Policy in Canada, Library of Parliament, Publication No. 2018-07-E 26, February 2018.

- Melanie Marten, Kurt van Dender: The use of revenues from carbon pricing, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No. 43.

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)