Anyone who has ever transferred funds internationally has encountered the high cost associated with these transfers. Banks charge a wire transfer fee, an exchange rate markup, and the recipient bank may add fees of their own. These fees are stupendous. They are also extremely profitable for our banks. Canadians who send money to family members abroad can end up with thousands of dollars in transfer fees in their lifetime.

Consider two typical Canadian banks. As of December 2019, Bank of Montreal charges $14 for incoming international wire transfers, and 0.20% for outgoing international wire transfers with a minimum fee of $15 and a maximum fee of $125. An extra "communication charge" of $10 may apply. The size of the exchange rate markup is more difficult to determine because the bank sets these rates separate from the market rates they pay for their own purchase or sale of foreign exchange. International transfers are expensive, especially when amounts are small. Are other banks cheaper? CIBC currently offers international transfers with what the claim to be "zero transfer fees" (CIBC Global Money Transfer). This offer comes with an important asterisk, namely that "CIBC foreign exchange rates apply." This means that customers still pay a fee, but they will be less likely to notice how much they pay because they cannot identify the bank's exchange rate mark-up easily. The bank's fees are simply rolled into the exchange rate mark-up, and whether CIBC is cheaper than BMO is difficult to ascertain without carrying out transactions simultaneously and comparing results. CIBC's offer appears to be more of an exercise in making visible fees invisible rather than truly lowering fees. Any offer of "zero fees" can never be true because banks still incur real costs that they need to cover. Between high costs and hiding fees, there is much scope for greater cost transparency. The European Union has indeed moved in that direction, and Canada should seriously consider following their example: require banks to fully and truthfully disclose their fees for international transfer. Only then can customers compare and make informed choices.

The Government of Canada states on its web page about Sending money to someone in another country that "banks and other federally regulated financial institutions in Canada must tell you how much they will charge you to send money abroad." That is true but incomplete because the total fees include the exchange rate mark-up. A few lines below the same web page states, correctly, that "some businesses make a profit on money transfers by charging a higher than usual exchange rate". Commerical banks do just that but they do not disclose the mark-up clearly. Thus the problem is with the lack of transparency for the full cost of transfers, everything included.

In December 2018, the European Commission and Parliament reached an agreement on cheaper cross-border payments and fairer currency conversions (amending Regulatoin 924/2009). The new rules provide for greater transparency for EU consumers, who are now able to compare currency conversion charges when making payments between Euro and non-Euro countries within the European Union. Consumers have a right to receive information about the currency conversion charges levied by their banks when sending money abroad. This mandatory cost transparency aims at countering opaque pricing methods for currency conversion.

While I have singled out Canadian banks above, I should note that some familiar international payment providers are not any better. Paypal, for example, adds 2.5% to wholesale exchange rates. This is roughly the same as many credit cards charge for currency conversions.

The high cost of international transfer has led to the development of novel business models for economizing on hidden foreign transfer fees. The model is based on the concepts of bilateral netting and multilateral netting, which has been widely used in multinational enterprises for decades and which I have been teaching routinely in my international business classes. Here is how they are defined:

Bilateral netting: The offsetting of payments between two parties so that the number and value of payments needed to settle a set of transactions is reduced. • Multilateral netting: The offsetting of payments among multiple parties to consolidate all incoming and outgoing payments into a single net position per party.

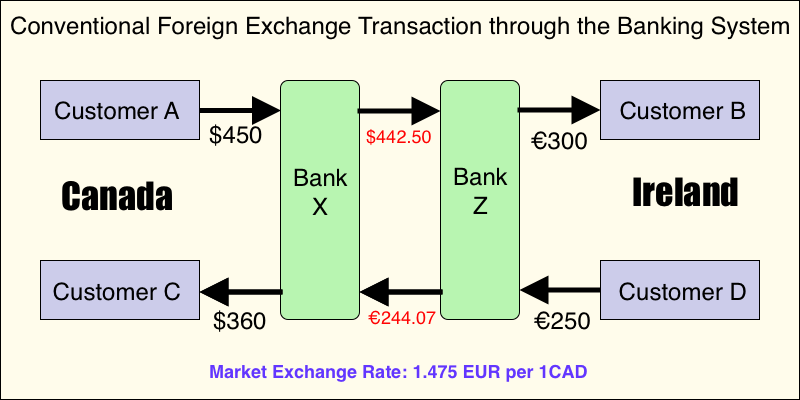

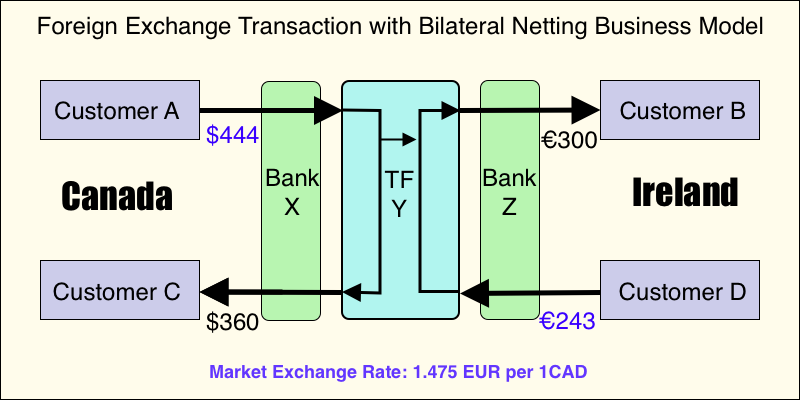

The next two diagrams show how it works in detail.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

Consider a conventional wire transfer through the banking system. Let's say customer A in Canada has to pay €300 to customer B in Ireland, and customer D in Ireland has to pay $360 to customer C in Canada. Assume that the mid-market exchange rate is 1.475 EUR per 1 CAD. That means that without fees, customer A would need to pay $442.50 and customer C would need to pay €244.07. However, Bank X applies an exchange rate of 1.500 instead of 1.475, and Bank Z applies an exchange rate of 1.440 instead of 1.475. This means that customer A pays $450 and customer D pays €250. In total, over $800 have been converted across the two transactions. Enter bilateral netting, carried out by transfer facilitator Y.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

In Canada, company Y receives offers a better rate to customer A, who pays only $444 instead of $450. Company Y disburses $360 to customer C in Canada (assuming no fees for using the interbank transfer within Canada). In Ireland, customer B receives the €300 oweed to them, while customer D pays €243 instead of €250. Company Y thus covers €243 out of the €300 from domestic sources, while only needing to convert €57 through open-market FX transactions. This netting out procedure saves an enormous amount of costs, as much less money needs to be converted on a daily basis. In the example above, customer A saves $6 in fees and cusomter D saves €7 in fess.

Of course, facilitator Y still pockets a small fee to cover its cost and make a small profit, but it will be able to offer a much better deal than banks X and Z because most of the transfers are domestic rather than international. This system works well as long as there are sufficient amounts of offsetting transactions that can be netted out this way. The period over which transactions are netted out are short. Facilitator Y will try to balance its books on a daily basis to prevent being caught on the wrong side of a currency movement.

There are indeed companies that pursue this business model, such as London-based TransferWise, a company founded by two smart Estonian entrepreneurs who realized the enormous business potential by offering cheaper international transactions. Recently, TransferWise even launched a petition to the Canadian Government to demand cost transparency for hidden fees similar to the regulations adopted in the European Union. Of course, greater transparency is to their advantage as they will benefit from cost comparisons. More importantly, greater cost transparency is beneficial to consumers, and thus the Government of Canada, as financial regulator, should have a much closer look at the experience in the European Union.

- European Commission: Cheaper Euro Transfers and Fairer Currency Conversions.

- Stuart Peters: TransferWise Consumer Research Canada, Consumer Intelligence Ltd., March 2019.

- Jordan Bishop: TransferWise Review: The Future Of International Money Transfers Is Here, Forbes, 29 November 2017.

- Venkat Srinivasan and Yong H Kim: Payments Netting in International Cash Management: A Network Optimization Approach, Journal of International Business Studies 17(2), Summer 1986, pp. 1-20.

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)