‘The world needs a a controlled re-entry agreement to prevent harm from rocket and space debris.’

Today UBC's Outer Space Institute (OSI) published an International Open Letter on Reducing Risks from Uncontrolled Reentries of Rocket Bodies, addressed to the heads of space agencies around the world. The uncontrolled re-entry of space debris and rocket launchers is posing a new, and potentially costly, hazard to all of us. Last year, roughly two-thirds of rocket launches to Low Earth Orbit (LEO) resulted in uncontrolled re-entries, and a significant share of their mass survives re-entry into the atmosphere. Even small fragments that make it to the ground can be large enough to cause serious damage. With rocket launches becoming cheaper and more frequent, we can expect the problem to grow significantly over the next decade.

Image Credit: European Space Agency

In July 2022, rocket debris from a Chinese Long March 5B heavy-lift rocket re-entered the atmosphere over the Indian Ocean. Yet, China's space authority even failed to share trajectory information with its international partners. On a previous test flight in 2020, things turned out much worse: a Long March 5B booster fell on villages in Ivory Coast in western Africa, causing some property damage but thankfully no injuries. And in November 2022, Spain had to close part of its airspace because another chunk of a Long March 5B was threatening flight routes. The European Union's Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) recommends flight restrictions on a 200 km-wide path around each of the re-entry passes of these objects of space debris. In busy air spaces around the world, re-entrant boosters and other heavy space debris is causing costly flight delays. Lack of information provided by some space agencies is also causing direct threats to life.

Estimates of risk need to explicitly take into account low-probability high-impact events such as debris strikes on aircraft in flight. Essentially, there are risk multipliers that change the calculation of potential harm. Conventional estimates do not take these into consideration. The economic cost of re-entrant space debris is much higher if we also count disruptions to economic activity such as civil aviation. Because of these indirect effects, what we see is a classic negative externality problem similar to environmental pollution. So what can be done to massively reduce the negative externalities from rocket launches?

The world urgently needs negotiations on a controlled reentry agreement. Rockets need to be equipped with the ability to control their re-entry, leaving sufficient fuel for re-entry burns that can control the re-entry trajectory. While some first-stage boosters can now be recovered safely, as is the case with Space-X's re-usable Falcon-9 boosters, second-stage boosters that make it into orbit will re-enter the atmosphere typically days after launch, and thus they need orbital manoeuvres to control when and where they re-enter the atmosphere. Obviously, this will add cost to the launches due to extra weight for the required fuel. But shirking this cost creates other costs down on Earth, first for civil aviation, and ultimately also for other types of damage, injuries, or even deaths. Such accidents are completely preventable. It will take space-faring nations to come to an agreement. The open letter concludes:

Simply hoping that uncontrolled reentries will not cause harm is an unsustainable strategy. With leadership, cooperation and global goodwill, these preventable and therefore unnecessary dangers can be greatly reduced.

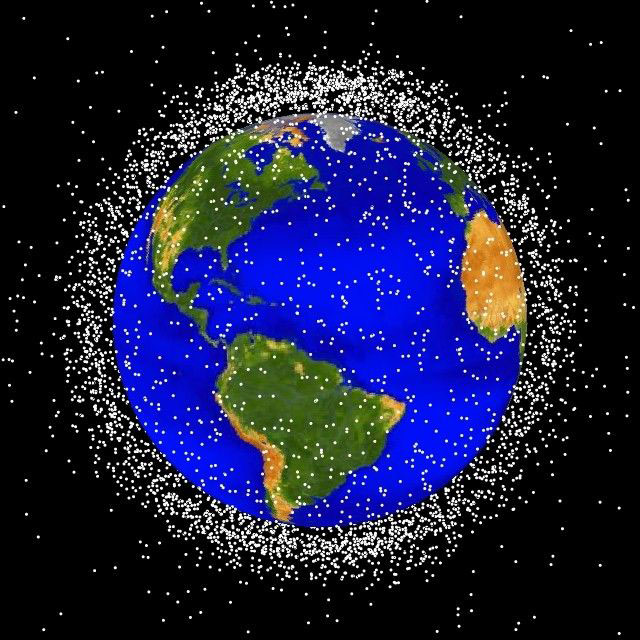

Image Credit: NASA

What are the practical solutions? First, avoid populated areas, or areas with high aviation or maritime traffic. There are some locations better than others. The best-known such location is Point Nemo, the point farthest from land in the South Pacific Ocean, which is also known as "the oceanic pole of inaccessibility." Second, design launch vehicles (mostly the second stages) in such a way that increases the likelihood of their full burn-up upon re-entry. Third, make liability explicit so that there is an economic incentive to invest in the first two solutions.

- Kenneth Chang: Debris From Uncontrolled Chinese Rocket Falls Over Southeast Asian Seas, The New York Times, July 30, 2022.

- Edward Helmore: Chinese rocket's chaotic fall to Earth highlights problem of space junk, The Guardian, May 8, 2021.

- Sam Jones: Spanish airspace partially closed as Chinese rocket debris falls to Earth, The Guardian, 4 November 2022

- Kenneth Chang: China Lucks Out Again as Out-of-Control Rocket Booster Falls in the Pacific, The New York Times, November 4, 2022.

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)