By international standards, milk is horribly expensive in Canada. This is a direct result of Canada's supply management system through which dairy production is controlled tightly, and prices are kept high. A one-litre carton of fresh 2% milk in a grocery store in British Columbia costs $2.89 (brand: Dairyland). In a grocery store in Germany, fresh 1.5% milk (brand: ja!) costs €0.99, that is $1.44—about half of the Canadian price. This is indeed the price that I paid during a recent visit. And German milk is just as good as Canadian milk, and it is also free of any rbST growth hormones exactly as in Canada.

Dairy producers in other countries have been trying to gain access to the Canadian dairy market, and in several rounds of trade negotiations Canada relented and agreed to open up its market a little bit. Under provisions of the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Canada-US-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), and the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement with the European Union (CETA), Canada has set aside a volume for imports through a system known as Tariff-Rate Quotas (TRQs). Simply put, a TRQ is a volume of imports that is not subject to tariffs, whereas near-prohibitive tariffs apply for volumes above the quota. TRQs are allocated to Canadian importers through a system controlled by the Government of Canada under the Exports and Imports Permit Act, and importers must respond to the annual Notice to Importers by applying for a share for each TRQ.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

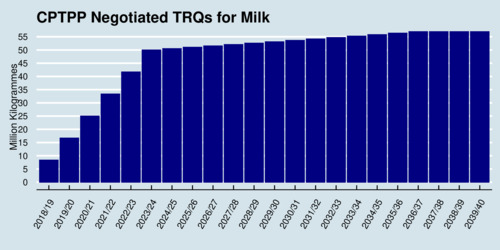

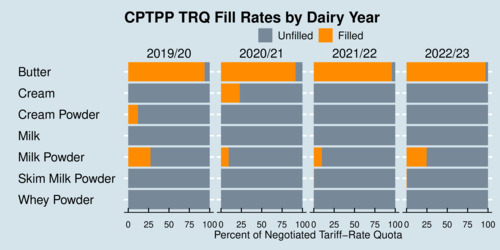

The CPTPP allows for milk imports to rise step-wise to just over 55 million kilograms, as the chart above shows. Quotas for other dairy products such as butter are defined as well. But something curious happened: much of the allocated quotas remained unfilled. Foreign producers, notably those in New Zealand, were unable to ship products to Canada. This meant that Canadian consumers were unable to purchase cheaper dairy products as intended by the trade agreement. The next chart shows the extent to which TRQs were filled over the last dairy years (which starts August 1 and ends July 31).

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

While producers in Pacific Rim countries were able to send butter to Canada, TRQs for milk, milk powder, and cream remained largely unfilled. Shockingly, not a single litre of milk was imported under the CPTPP TRQ in 2022/23. It is thus no surprise that New Zealand and other countries filed a complaint in May 2022 under the CPTPP dispute resolution mechanism to challenge Canada's subterfuge that has kept foreign milk out of Canadian grocery stores.

New Zealand's complaint centered around a provision through which Canada's CPTPP TRQs are allocated to three types of importers: processors, further processors, and distributors. This is known as a "pooling system", as these types of importers form a "pool" for allocation purposes. The bulk (80-85%) of TRQs were allocated to processors, which created a new import barrier. Canadian processors could reap all the benefits from the cheaper imports and continue selling dairy products at the controlled Canadian prices. Retail importers (distributors) were thus not able to buy cheaper milk from New Zealand and sell it to their customers at a lower cost.

The CPTPP has a provision that is referred to as the "Processor Clause" 2.30(1)(b) which was meant to limit the preferential allocation to processors. Canada disputed this because there was some share of TRQs that non-processors were eligible to obtain. However, the CPTPP panel determined that Canada breached its trade commitments. The panel concluded that "reserving access to specific percentages of its TRQs for processors is inconsistent with Canada's obligations under Article 2.30(1)(b)". The spirit of the CPTPP is that the agreement should be administered in such a way that it allows importers to utilize the TRQ quantities fully. The panel found that Canada's TRQ pooling system is incompatible with this obligation.

So where will Canada go after this ruling? The government appears to double down. Rather than acknowledging Canada's failure to adhere to CPTPP rules and remove the trade barriers, the government released a statement promising that "we will not negotiate these [TRQ] allocations with countries who seek to weaken Canada's supply management system." Will Canada try to defy the spirit of the panel's ruling and find new ways to cripple dairy imports?

Notably, a dispute settlement under CUSMA reached similar conclusions as the CPTPP panel. Canada removed the CUSMA dairy pools. But that did not satisfy the United States, as they launched a new challenge. Whether a new dispute resolution panel is convened is not yet determined. After the CUSMA panel's decisions, the CPTPP panel's decisions is the second ruling against Canada. Canada cannot continue entering into trade agreements promising to open up its dairy industry and then turn around and slam the door shut by using subterfuge and chicanery.

Canada's supply management system for dairy products remains politically untouchable. No major political party in Canada is willing to even discuss reform. Opening up small slivers of the dairy market to foreign competitors by way of TRQs has been a very modest concession. The industry was amply compensated with government largesse to address the impacts of CETA, CPTPP, and CUSMA. Overall, the Government of Canada is providing a further $1.7 billion in direct payments and investment programs to compensate supply-managed sectors, bringing the total to $4.8 billion.

Reform of Canada's supply management system is not impossible. The dairy industry sees imports largely as a threat. But opening up export markets for Canada's dairy industry could ultimately also create new opportunities, and new-found efficiencies would allow the industry to defend their market position against competitors. Consumers could benefit through lower prices, and producers through new export markets. McLachlan and van Kooten (2022) conclude in their research paper:

The benefits of restricting milk output accrue to very few in society, while imposing a large burden on consumers, especially the poorest in society. With the exception of a few dairy producers who have benefitted from rising quota values, even farmers themselves are harmed by a dairy quota regime as they carry unnecessary debt, have difficulty expanding output to take advantage of economies of scale, and are unable to take advantage of potentially lucrative export markets.

The cost of suppply management to consumers is significant. Cardwell, Lawley, and Xiang (2015) found that the supply management system is highly regressive, imposing a burden of approximately 2.3 percent ($339) of income per year on the poorest households, compared to 0.5 percent ($554) for the richest households. Of course, today's dollar figures will be higher due to inflation; roughly 29% since the study was published.

That reform is possible is shown by Australia's deregulation of its own supply management system in 2000. The phase-out occurred gradually, with farmers receving government assistance during the lenghty transition period. Of course, some dairy farms exited, while others consolidated and expanded. According to data from Dairy Australia, average herd size has grown to 303 in 2022 (up from 93 in 1985, similar to where Canada's average herd size is today). Since the reforms started, the number of Australian dairy farms has decreased quite dramatically from nearly 12,896 in 2000 to 4,420 in 2022. However, overall milk production and exports have changed very little. International farmgate milk prices in Australia, New Zealand, the UK and the EU hover between USD 40–45 per 100kg; in Canada, it is USD 60/100kg. Canadian farmgate milk prices are 35-50% more expensive than in other developed countries.

Returning to the two CPTPP and CUSMA trade rulings, the Government of Canada has suffered two significant defeats in quick succession. The federal government must stop prevaricating and instead live up to its international trade obligations fully and comprehensively. Allowing foreign producers to fill the TFQs fully will benefit consumers, while Canadian producers have been compensated generously already, at great cost to Canadian taxpayers.

Sources and References:

- Alan Kenigsberg, Brad Wall, Chelsea Rubin, and Valeska Rebello: CPTPP panel releases decision on Canada's practices regarding allocation of dairy tariff rate quotas under Agreement, Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, 14 September 2023.

- CPTPP Dispute Resolution Panel: Canada — Dairy Tariff Rate Quota Allocation Measures, Final Report, 5 September 2023

- Government of Canada: Supply-managed tariff rate quotas (TRQs), Utilization Data.

- Alan Kenigsberg, Brad Wall, Malcolm Aboud, and Chelsea Rubin: CUSMA panel issues decision on Canada's interpretation of dairy tariff rate quotas under Agreement, Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, 7 January 2022.

- CUSMA Arbitral Panel: Canada — Dairy TRQ Allocation Measures, Final Panel Report, December 20, 2021.

- Richard Barichello, John Cranfield and Karl Meilke: Options for the Reform of Supply Management in Canada with Trade Liberalization, Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques 35(2), June 2009, pp. 203-217.

- Brennan A. McLachlan and G. Cornelis van Kooten: Reforming Canada's dairy supply management scheme and the consequences for international trade, Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics 70(1), March 2022, pp. 21-39

- Ryan Cardwell, Chad Lawley, and Di Xiang: Milked and Feathered: The Regressive Welfare Effects of Canada's Supply Management Regime, Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques 41(1), March 2015, pp. 1-14.

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)