One of the consequences of transitioning from internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) to battery electric vehicles (BEVs) or plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) is the drop in gas tax revenue, which includes the components that support Translink (within the South Coast British Columbia service region, SCTA) and BC Transit (in the Victoria area). Fuel taxes on gasoline in British Columbia are composed of a 6.75 cents/liter (¢/L) tax that supports the B.C. Transportation Financing Authority; an 18.5 ¢/L charge for Translink or a 5.5 ¢/L charge for BC Transit; and 7.75 ¢/L general revenue across the province except for the Vancouver area, where it is only 1.75 ¢/L. Put another way, motor fuel taxes sum up to 27 ¢/L in Vancouver, 20 ¢/L in Victoria, and 14.5 ¢/L in the reset of the province.

Overall gasoline sales in British Columbia do not appear on a major downward trend yet, and thus it is not clear if electrification of mobility has a major impact. In the last pre-pandemic year 2019, 4.822 billion liters of gasoline were sold in BC, according to Statistics Canada [23-10-0066-01]. In 2022 that number had dropped to 4.717 billion liters; a 2.2% drop over 2019. Data for 2023 were not yet available. Population increased from 5.111 million in 2019 to 5.356 million in 2022, so on a per-capita basis fuel consumption dropped from 943 liters per person per year to 881 liters, a 6.6% drop. If this trend persists, and electrification accelerates, we should see larger changes in the next few years. This could spell problems for revenue streams.

Revenue projections in Translink's 2023 budget are based on 1.758 billion liters of fuel consumption in the region (about 37% of the provincial total), which are expected to generate about $325 million in revenue from gasoline and about $400 million in total (including diesel). If fuel consumption starts to shrink due to electrification, a significant part of this revenue is in jeopardy. BC needs to look at alternative forms of taxation to make up the shortfall. There is good reason to keep collecting revenue from motor vehicles due to the urban externalities that are associated with them.

Economists have been investigating two major alternative revenue sources to complement and eventually replace dwindling motor fuel taxes. The first is a Vehicle Kilometers Traveled (VKT) tax [in the US of course known as a VMT tax]. The second is congestion charges that are specific by time and location. Congestion charges have not advanced in BC although they were discussed extensively in a report to the Metro Vancouver mayors. VMT taxes are already springing up in parts of the United States as experiments or programs (see Garret Shrode's survey from August 2023).

The key argument in favour of a VKT tax is that it is usage based: the more you drive the more you pay. The average motorist in BC purchases about 1,080 liters of gasoline per year, give or take. Translink's 18.5 ¢/L charge amounts to roughly $200 per year in revenue that would need to be replaced if gasoline use completely disappeared. More realistically, let's assume that we need to replace only 25% of gasoline revenue with a VKT by 2030, which would be equivalent to an $50/year on the average motorist in the Metro region. If the average motorist drives about 12,000 kilometers per year, the fee should be 0.42 ¢/km (equivalent to about 14¢/day).

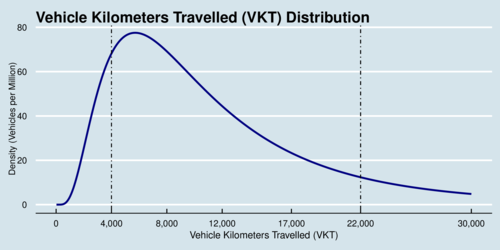

What would actual VKT tax schedules look like? The simplest version is the flat rate described above: divide the required revenue rate per driver by the average annual VKT. However, policy makers may also worry about affordability, protecting certain groups of motorists, covering administrative overhead, and discouraging under-reporting of VKT. Policy makers may therefore look to non-linear VKT schedules with a lower and upper VKT threshold. For that purpose it is necessary to know the distribution of VKTs. The diagram below shows a log-normal distribution of VKTs with a mean of 12,000 kilometers and a coefficient of variation of 0.8. The diagram also shows two thresholds at 4,000 km and at 22,000 km, which cover roughly 11% each of the lower tail and the upper tail of the distribution.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

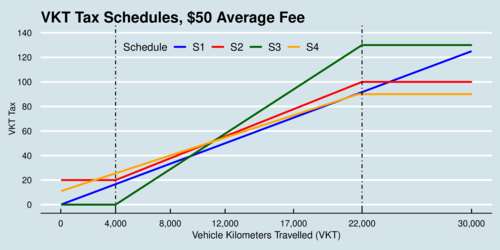

The second diagram explores four different VKT tax schedules. All four schedules generate roughly the same $50/year revenue. The first tax schedule (S1) is the blue line with the flat rate of 0.42 ¢/km. Motorists who have very high VKTs may end up paying proportionately high fees, and policy makers may worry about the financial impact on households that commute to work long distance. Thus capping the top 11% of the distribution (over 22,000 kilometers) may be a policy option. Schedules S2, S3, and S4 all have caps at that VKT level. Schedule S2 (red line) also has a minimum fee of $20/year for all motorists, regardless of VKT. Thus a price cap of $100/year can be set on the other end. Schedule S3 (green line) protects low-VKT households by setting a zero fee for the first 4,000 kilometers. This policy could be useful if low-VKT households are mostly elderly drivers on a fixed income. If this group is protected, then the cap at the other hand needs to be raised to $130/year to generate the desired revenue. If protecting low-VKT drivers is not needed, tax schedule S4 (orange line) imposes only an upper threshold, starts with a minimum fee of $11 and sets a maximum fee of $90 in order to reduce the burden on the high-VKT drivers.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

The discussion above shows that VKT taxes can be adjusted in numerous ways to accommodate various policy concerns and improve political acceptance of a VKT tax. There are other dimensions in which VKT taxes can be differentiated as well. For example, VKT rates could differ by weight class of a vehicle, with higher rates for heavier vehicles.

A VKT tax only focuses on negative externalities from driving that are proportional to the distance driven. But not all externalities are simple functions of driving distance. Congestion pricing is favoured by economists because it can address congestion externalities that are time-dependent and location-dependent. The appeal of a VKT tax is the relative simplicity of administration. If odometer readings are reported once a year to the government (through the required insurance renewal), that is sufficient to assess the VKT tax that is due. Instituting congestion pricing requires more information as it is necessary to identify when and where a vehicle is driven. Odometer readings are much less intrusive in terms of information requirements.

This blog is titled "Will BC need to transition fuel taxes to VKT taxes?". Arguably, the question is not about "if" but about "when" a VKT tax will be needed. If the transition to electric vehicles speeds up and revenue streams dwindle, then a VKT tax needs to be phased in gradually to make up for the fuel tax shortfall. However, BC should not lower fuel tax rates along the way. Today's fuel tax rates help propel the EV transition. As a VKT tax ramps up gradually, it falls on all drivers regardless of propulsion system. Thus introducing a VKT tax will not diminish the cost gap between ICEVs and BEVs. Instead, drivers of BEVs and PHEVs will continue to enjoy a significant cost advantage.

Some economists have argued that a VKT tax should only be applied on drivers of electric vehicles rather than drivers of ICEVs. The argument hinges in part on the observation that today electric vehicles are more likely found in affluent households, and thus the existing motor fuel tax is exaggerating the general income-regressivity of that tax. My colleagues Davis and Sallee (2020) reported on this phenomenon, based on US data. They found something rather interesting. While some US states have adopted VMT taxes for electric vehicles (US1.7¢/mile, about C1.4¢/km) in lieu of their local gasoline tax, Davis and Sallee find that "it is not even clear based on our analysis whether the optimal mileage tax for electric vehicles is positive or negative." They also argue: "As long as gasoline is priced well below social marginal cost, it is probably not efficient to tax electric vehicle mileage because this leads to substitutio toward gasoline vehicles." Thus instituting a VKT tax should not be a replacement for fuel taxes, bur rather a necessary augmentation.

- Ashley Langer, Vikram Maheshri, and Clifford Winston" From gallons to miles: A disaggregate analysis of automobile travel and externality taxes, Journal of Public Economics 152, 2017, pp. 34-46.

- A. Rodriguez and S. Pulugurtha: Vehicle miles traveled fee to complement the gas tax and mitigate the local transportation finance deficit, Urban, Planning and Transport Research 9(1), 2021, pp. 18-35.

- Y. Wang and Q. Miao: Implication of Replacing the Federal and State Fuel Taxes with a National Vehicle Miles Traveled Tax, Transportation Research Record 2672(4), 2018, pp. 32-42.

- Lucas W. Davis and James M. Sallee: Should Electric Vehicle Drivers Pay a Mileage Tax?, Environmental and Energy Policy and the Economy 1, 2020.

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)