‘Voters deserve clear information from all political parties about which climate policies they embrace—not just those that they don't.’

Conservative politicians in Canada are campaigning to end the federal carbon pricing backstop as well as provincial counterparts. Carbon pricing is the center piece of climate action in Canada. Would the demise of carbon pricing for consumers mean the end of all meaningful climate action in Canada? So far, conservative politicians have been less than forthcoming with information about which climate action policies they embrace; they have only been clear about the one policy that they want to abolish. Even that proposition is a bit vague. They are not clear if they would keep a carbon price on industrial emitters (such as power plants, refineries, natural gas liquefaction plants, steel plants, cement plants, etc.) and only end carbon pricing for households (mostly for transportation and home heating). Would conservative politicians in Canada roll back other climate policies as well? To be fair, in recent days the federal NDP announced their opposition to the current carbon pricing system, coupled with somewhat nebulous statements (lacking specificity) about making large emitters "pay their fair share". Meanwhile federal Liberals have backtracked on carbon pricing with their October 2023 announcement of a three-year exemption for carbon pricing home heating.

The lack of clear answers from politicians is deeply troubling in the presence of a climate crisis. The scientific facts about climate change are clear, and the effects of climate change can be felt across the country. Voters in Canada deserve clear answers from politicians of all stripes about what they intend to do about climate change.

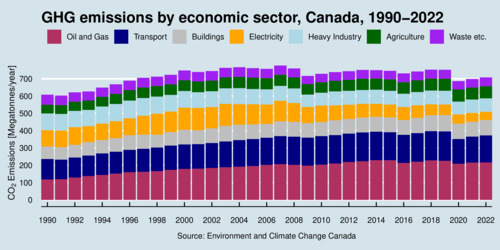

Textbook economics has a straight-forward answer for dealing with pollution: put a price on it that equals marginal damage. In the context of greenhouse gas emissions, this means putting a price on these emissions equal to the social cost of carbon, which is an estimate of the marginal damage. Canada's carbon price is currently $80/tonne, which translates into 17.8 cents per liter of gasoline. Carbon pricing on motor fuels seems to have had just enough of an effect to keep overall GHG emissions from transportation level, with improvements in fuel efficiency (including adoption of electric vehicles) just compensating for increased transportation demand from a growing Canadian population. Canada's annual greenhouse gas emissions are seemingly stuck at about 700 Megatonnes (see diagram below), with only the pandemic creating a small downward blip.

click on image for high-resolution PDF file

Federal carbon pricing is a two-part system: it puts a marginal price of $80/tonnes on carbon, and then it redistributes the revenue from carbon emitters to households on a per-capita basis (with small adjustments for family size, and differentiated by province). This is now named, belatedly, the Canada Carbon Rebate. As a result, low-income households that typically have a low carbon intensity are net gainers financially, as they receive more money through the rebate than the pay through the price on carbon. Households with a high carbon intensity end up net payers. Federal carbon pricing is intended to be roughly revenue neutral, and it addresses the income-regressivity of government levies on energy. Without the rebate system, a carbon price would put a heavier burden on low-income households because their energy expenses are a larger share of their budget than it is the case for high-income households. Pollution pricing coupled with revenue rebates are textbook economics solutions that achieve efficiency and fairness at the same time.

The federal carbon pricing system is not a tax in the classic sense: it is not intended to generate general revenue. Instead, it is a redistribution system that disincentives carbon pollution and in turn incentivizes improvements in energy efficiency. Conservative politicians purposefully mischaracterize carbon pricing as if it was a conventional tax like the General Sales Tax [GST]. Calling it a tax doesn't make it a tax. Pierre Poilievre's "axe the tax" rhetoric could be rephrased, with equal justification as a description of the intended policy change, as "vacate the rebate" or "defund the refund". Not as catchy, I admit, but it correctly describes the other side of the coin. Heads or tails? Take your pick.

‘Ending consumer-side carbon pricing will not make everyone better off; instead there will be winners and losers, and the winners are mostly affluent households.’

So what is the problem that conservative politicians have with carbon pricing? After all, this system lets the market figure out the optimal response to the carbon price, rather than government regulation telling households and industry what each should do. Regulation tends to be more costly than market-based instruments. Conservative politicians seem to be enamored with low energy prices, particularly the price at the pump for gasoline and diesel. Chop off 18 cents per liter: what's not to like about cheaper gas? Conservative politicians certainly believe they have a political winner with their full-throated opposition to carbon pricing. But then again, the same would be true for any tax cut. Why not slash the GST by another two percent as Steven Harper did? Who doesn't like to pay less for everything? But wait, not so fast: who is going to make up the shortfall for the lost revenue? Canada's carbon pricing system is an easy political target because it is essentially revenue neutral. It doesn't affect the budget balance, and discontinuing it would not blow a new hole in the federal budget. Instead, it will make affluent (and some rural) households better off, and most low-income (and mostly urban) households worse off. An end to consumer-side carbon pricing would create winners and losers.

If conservative politicians had said: "today's carbon pricing system is not delivering results fast enough and we have a better plan without consumer-side carbon pricing", I would have been rather interested. There are in fact valid criticism about our current approach to carbon pricing, and consumer-side carbon pricing in particular.

First, the carbon price of $80/tonne in 2024, and the targeted carbon price of $170/tonne in 2030, are well below what the scientific community has established as the social cost of carbon. The best estimate seems to be US$185/tonne, or about $250/tonne. So today's carbon price is only about one-third of what it needs to be to tackle climate change. As a result we have seen "policy stacking", the deliberate combination of multiple policies in order to get us closer to the intended emission reductions.

Second, carbon pricing struggles to get the intended environmental results when people are price-insensitive in usage of existing technology and face difficulties making decisions about investing in new technology. The carbon price on gasoline affects the usage decision directly. If you drive a gas-powered car, you'll drive it a little less if the price of gasoline goes up—but not by much because the demand for transportation is relatively price-inelastic. So the environmental gains here are small. However, a higher price of gasoline should affect your decision when buying a new car: buy a more fuel-efficient conventional car, or buy an electric car, and you remissions will be much lower for the lifetime of the new vehicle. The emission savings from going electric are where the real action is. Unfortunately, consumers are often myopic when they make long-term investments and focus more on the sticker price than the total life-cycle costs (which includes the effect of the carbon price over the lifetime of a vehicle). This is a classic economic problem known as capital bias. Incentivizing adoption of cleaner technology more directly, through subsidies, can overcome the capital bias problem.

There are three potential problems with subsidies. First, you need a baseline against which you measure a reduction or change. That's easy if it's a discrete choice because we know the vehicle or furnace that someone is replacing. Establishing a baseline is much harder when it involves past usage, which can be manipulated or inflated. Second, the more successful a subsidy scheme, the more expensive it becomes, and the more revenue a government needs to raise to pay for it. Third, when subsidies are used for a decision such as buying an electric vehicle, the subsidy is fixed irrespective of how much the vehicle is used (and emissions avoided). Purchase subsidies are only indirectly linked to the intended emission reductions. There is thus only a narrow set of applications where subsidies can be as effective as putting a price on the observable pollution.

‘Meaningful climate action for households can succeed without consumer-side carbon pricing—but only if other key climate policies survive.’

But there is potentially some good news. The end of consumer-based carbon pricing does not need to spell the end of meaningful climate action for households. Several policies will remain pivotal. First is the Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) mandate, which requires car makers to shift to selling only battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) by 2035. If this mandate remains, we will see a significant shift to EVs and in turn significantly lower carbon emissions. The ZEV mandate is not necessarily a free lunch economically. If battery prices drop sufficiently fast to make EVs cheaper than conventional cars, it would eventually amount to an economic and environmental win-win for consumers. On the other hand, if innovation is too slow and battery prices don't come down fast enough, motorists will face more expensive vehicle purchases (although lower operating costs because electricity is much cheaper than gasoline). The ZEV mandate will thus have an implicit carbon price. The good news, though, is that the trajectory of battery prices is clearly downwards. The ZEV mandate, should it remain in place, can have a much stronger effect than carbon pricing. Subsidies for EV purchases may continue to boost early adoption, but eventually will need to be phased out as they become unaffordable. Canada cannot afford to subsidize every car purchase at the tune of $5,000 to $9,000 (combining federal and provincial incentives) indefinitely.

The second important climate policy is the biofuels mandate, known as the Clean Fuels Regulation federally and as the Low Carbon Fuels Standard in BC. Both aim to increase the blending of biofuels into regular fuels. Motorists across the country already buy mostly E-10 as regular fuel, that is regular gasoline blended with up to 10% of ethanol. The development of biofuels is making significant strides, with second generation biofuels such as renewable diesel (RD) already firmly on the horizon and with larger greenhouse gas reductions than first-generation biofuels such as ethanol. Biofuels can help reduce carbon emissions of the existing combustion engine vehicle fleet (although biofuels have some environmental and economic issues of their own).

The third policy targets home heating through subsidizing the purchase of heat pumps as replacements for oil and gas furnaces. These subsidies can be customized to what is being replaced, knowing that heating demand is price-inelastic. Households that are unable to switch their heating system would obviously benefit from a discontinuation of carbon pricing, but they would now lack the incentive to switch to a cleaner heating system as well. Heat pumps even work well in cold climate, while life-cycle savings may differ regionally depending on local fuel and electricity prices. Without consumer-side carbon pricing, regionally-differentiated subsidies that are conditioned on what heating system is being replaced could be highly effective as a policy alternative.

The fourth essential element is a shift towards increased public transit in urban areas. There are various economic policies that can achieve that. The equation is simple: fewer cars = fewer emissions.

If conservative politicians succeed in ending consumer-side carbon pricing in Canada, I hope that they will embrace alternative climate action policies. As I have discussed above, some may even work just as well or even better. If, on the other hand, conservative politicians dismantle other essential climate action policies as well, the only game in town that's left is rapid innovation. The moment EVs are broadly cheaper than gas-powered cars, the decline of the the oil industry is inevitable. That point is well in sight. Wind and solar power have already become cheaper than most fossil-fuel alternatives, and the emergence of cheap grid-scale batteries will seal the deal for renewables. So whatever politicians may be up to, ultimately market forces will drive the energy transition with or without them.

Lastly, what would happen in BC if carbon pricing is discontinued? BC's premier announced that BC would align policies with the federal government. But BC's carbon pricing is more complex than the federal system because carbon pricing in BC started out as revenue neutral through income tax cuts and a sales tax credit. Under the provincial NDP government, a climate action tax credit for eligible low-income families. If consumer-based carbon pricing was rolled back in BC, the tax credits would disappear, making life less affordable for many low-income households; about 65% of British Columbians receive the climate action tax credit. Would it also mean rolling back the initial tax cuts introduced by the BC Liberals in 2008? What would make up for the revenue shorfall? The estimated carbon tax revenue for fiscal year 2024/25 is $2.565 billion, while $1.022 billion is expected to be paid out through the Climate Action Tax Credit. The 2024/25 budget also contains $384mio in funding for CleanBC grants and rebates. If this funding is included, the overall design makes the carbon pricing system in BC effectively revenue neutral. (N.B.: The $35/tonne carbon price under the BC Liberals was legislated to be revenue neutral; in today's terms that means revenue of $1.443 billion comes from the difference to the current $80/tonne; deduct the climate action tax credit and CleanBC funding, and the result is effective revenue neutrality.) There is little doubt here that a discontinuation of consumer-side carbon pricing will tear a big hole in the provincial budget. Politicians arguing for a discontinuation of carbon pricing should clearly state how they would address the shortfall: raise taxes, cut expenditures, or increase public debt?

Whatever happens to consumer-side carbon pricing, it is crucially important to keep carbon pricing for industrial emitters as they do not face the same challenges as households when responding to carbon prices. Industrial carbon pricing is quite effective as businesses have the ability to respond to carbon pricing through investments in abatement and new equipment. However, even for industrial carbon pricing there are different models of implementation. Quebec has cap-and-trade system (joint with California), where caps are fixed and prices emerge through the market. As Europe's Emission Trading System shows, after some initial hickups getting the system started, it is now in Phase IV and the emission cap continues to decline annually and linearly by 2.2% per year between 2021 and 2030. Even non-EU countries link to the system, including Iceland, Norway and Switzerland. There are several viable and effective models for putting a price on carbon emissions from industrial emitters.

There is a climate crisis. Climate action is needed desparately. Economics tells us the direction we need to take, and how to do that effectively, efficiently, and fairly. We can debate about the best way to achieve these policy objectives, but climate policy inaction and climate science equivocation are simply unacceptable. The world and the climate conditions that our children and grandchildren will live in depends on our policy choices today.

• • •

This blog was updated on October 18, 2024 to correct an error in the size of the BC Climate Action Tax Credit and use the estimated numbers for the current fiscal year 2024/25. The update also provides the calculation for the implied "effective revenue neutrality" of the current carbon pricing system.

Updated on Friday, October 18, 2024

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)