The United States launched a perfidious, irrational, and harmful trade war against Canada in early 2025. Canadian province have retaliated by limiting imports of beer, wine, and liquors from the United States. How are things shaping up since? The quick answer: Canadians are not going thirsty. Canadians can do just fine even without American booze. No sweat.

As a trade economist, I have been pouring over numerous charts every month tracking the effect of the trade war, focusing mostly on the harm caused by U.S. tariffs on Canadian exports. Canada's retaliation has been most noticeable with respect to alcohol imports as these imports are largely administered by provincial liquor control boards. Four charts below show where things have ended up by the end of summer.

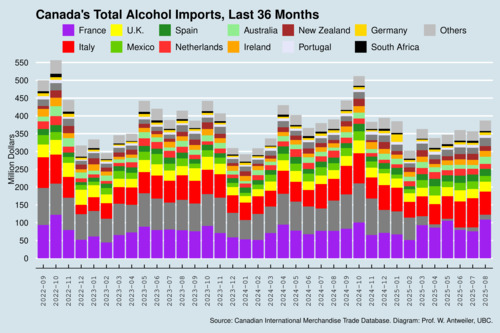

The first chart shows Canada's total imports of alcohol across the three major harmonized system (HS) codes for beer (2203), wine (2204), and liquors (2208) such as whiskey. As can be seen clearly, overall imports have not dropped. Imports from the United States have been squeezed out and have mostly been replaced with imports from other countries. I do not have data on how Canadian alcohol producers have fared, but it is safe to conjecture that their sales have increased as well. However, as imports have been stable overall, the shift away from U.S. imports has most likely gone to other foreign producers.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

‘Canadians are drinking more French and Italian wine instead of American wine.’

I estimate that monthly imports from the U.S. have declined by about 69.6 million dollars between March and August of 2025. The countries that have gained the most are France (+$13.9mio) and Italy (+$8.4mio). Spain, New Zealand, Chile, and Ireland all gained about 3 million dollars. French and Italian vintners will be happy. Perhaps Canadians will relieve their sorrows about the economic impact of the trade war with an extra glass of Chianti from Tuscany or a Chardonnay from Burgundy.

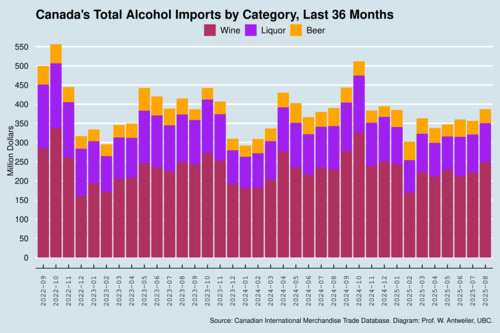

The next chart shows that the mix of imports has not changed much. Canada's alcohol import is mostly wine, followed by liquors, and not much beer. Beer is mostly brewed domestically, and imports are mostly from countries that brew distinct flavours such as Irish stout. Sláinte to a frothy Guinness and a creamy Smithwick's. And Prost! to a cloudy Hefeweizen from Bavaria. Who needs American beer when there is so much wonderful variety from Europe?

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

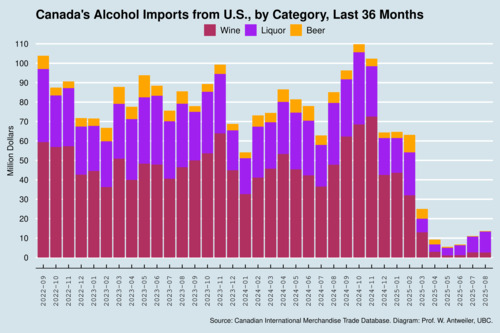

Let's have a closer look on imports from the United States, which typically runs to 80-100 million dollars every month. As the next chart shows, provincial import restrictions have had a spectacular effect. Imports of wine and beer have pretty much collapsed, but imports of liquor have crept up a bit since March. Where are these liquors going? In August, Alberta accounted for half of alcohol imports from the United States. You can draw your own conclusions from this observation.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

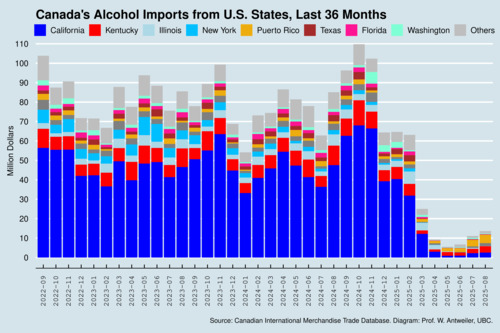

But who are Canadians sending a message to with their reduced alcohol imports from the United States: blue (Democratic) states or red (Republican) states? My final chart decomposes alcohol imports by origin state. I use blueish hues for the Democratic-leaning states (California, Illinois, New York, and Washington) and reddish hues for the Republican-leaning states (Kentucky, Texas, and Florida). And there is also Puerto Rico.

click on image for high-resolution PDF version

‘Canada's liquor retaliation hurts blue states more than red states.’

Most of Canada's imports of alcohol from the United States arrives from the Golden State: California, which is known for its vineyards in the Napa and Sonoma valleys. Kentucky is the second-largest exporter state, and Kentucky is known for its whiskey and bourbon. My sense is that provincial restrictions on alcohol imports from the United States may be mostly hitting the wrong geographic target. Alcohol imports from red states are the smaller part of the import profile. Perhaps targeting just whiskey and bourbon would be more effective than targeting wine and beer.

Retaliation in a trade war always comes at a cost. In the case of alcohol, this cost is rather small as there are plenty of excellent substitutes. Retaliation is meant to send a powerful message to the decision makers, and thus needs to be sharp and pointed — and typically time-limited. The only problem is that the man in the White House probably doesn't get the message. A known teetotaler, the U.S. president has no vested interest in the alcohol industry in the country.

There are no winners in a trade war. Pain is not felt in Canada alone. Industries in various U.S. states are hurting too. Has the protection of domestic U.S. industries done much good? The little gains come at a great cost. The trade war threatens to disrupt American firms' global supply chains and has harmed the reputation of American firms as trustworthy business partners. And how much pain has the trade war inflicted on U.S. consumers already? The pain of higher prices will become more obvious as American consumers have started shopping for their Christmas gifts. In October, the Peterson Institute for International Economics reported results from their economic model projecting that the trade war will increase inflation and slow economic growth in the United States. The Budget Lab at Yale University reported that average import tariffs in the United States are now hovering near 18%, a level not seen since 1934. The end of the trade war will only arrive when American voters make it clear at the ballot box that they have had enough of higher prices—and of erratic trade policies. Canadians need to remain patient while we bide our time, allowing the federal government in Ottawa to work quietly to engage in damage control. It's neither "elbows up" nor "elbows down" for Canada; it's much more "elbow grease" to protect the future of the Canada-US-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA).

![[Sauder School of Business]](logo-ubc-sauder-2016.png)

![[The University of British Columbia]](logo-ubc-2016.png)